This year celebrates the 500th anniversary of the death of Luca Pacioli. A mathematician as well as a friar –a Franciscan in this case– he was linked to two of the greatest artists of the Renaissance: Leonardo da Vinci and Albrecht Dürer.

Pacioli was born in Borgo Sansepolcro in 1445. In 1494 he published in Venice his huge Summa de arithmetica, geometria, proportioni et proportionalita, the great mathematical encyclopaedia of the 15th century. It included a part focused on the mercantile applications of arithmetic, entitled De computis et scripturis. It is perhaps an exaggeration to say that, with De computis et scripturis, Fra Luca Pacioli invented modern accountancy, even if this is such a modest and skeletal exaggeration that it can almost be considered as equanimous. Perhaps as much as to say that his influence has survived into the 21st century, helped in part by the translations into so many languages that De computis et scripturis has had.

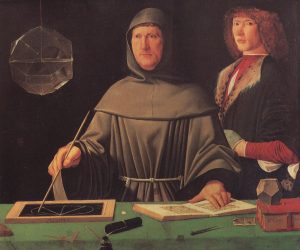

Pacioli commissioned a portrait –attributed, dubiously, to Jacopo de Barbari. If we consider it the portrait of a friar, it is not much –the great and not so great art galleries are full of portraits of friars much better than Pacioli’s– but if we consider it the portrait of a mathematician, then it is undoubtedly the most flattering portrait that any mathematician has ever had done –which is perhaps of little merit given the scarcity of the genre: in it, Luca Pacioli poses in unmistakable Franciscan garb, including a somewhat tight-fitting hood; but he is neither praying nor meditating and, contrary to Franciscan rule, he exhibits in his portrait what was perhaps one of his most prized possessions: for Pacioli poses next to his Summa de arithmetica. Pacioli preferred to be portrayed teaching, not the revealed truths of the Gospel, but the demonstrated truths of Euclid’s Elements, which is the book on which his left hand rests, while with his right he wields a baton with which he seems to conduct an orchestra of geometric lines dancing on a blackboard. The painting is no stranger to a good pinch of poetry, which is also a truth, but neither revealed nor demonstrated, but unprovable. There are those who maintain that the curly-haired young man who accompanies him is his lover, although this is probably the slander of some anti-clerical. The fact is that his identity is not known with certainty; perhaps he is Guidobaldo de Montefeltro, Duke of Urbino, whose tutor was Pacioli, although some have suggested that he could well be Albrecht Dürer.

In 1496 Pacioli arrived in Milan as a mathematics teacher, and there he joined Leonardo da Vinci during the latter’s last years in the service of Ludovico Sforza; both fled the city in 1499, after it was conquered by Louis XII of France.

While in Milan, Fra Luca Pacioli wrote another book, although this one is quite different from his Summa: it is De Divina Proportione, the manuscript of which he had already finished by the end of 1497. De Divina Proportione is a treatise on the golden ratio, where the mystical and esoteric also has a place; strongly influenced by Pythagoras and Plato, the work postulates the pre-eminence of mathematics over other disciplines because everything “is necessarily reduced to number, weight and measure”.

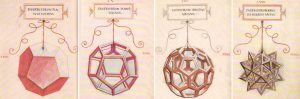

Leonardo da Vinci left his mark on De Divina Proportione, certainly in the text, which owes much to their conversations and, above all, in the 60 drawings of polyhedra “by the hand of Lionardo da Vinci” that are included, polyhedra that he drew in solid form but also showing their internal structure.

Pacioli’s work went to press in 1509. To the original text written by Pacioli and Leonardo’s drawings were added a few more treatises on architecture and other subjects, including an Italian translation of the manuscript Libellus de quinque corporibus by Piero della Francesca; Pacioli and della Francesca were born in the same village, the former 25 years after the latter, and there they formed a cordial pupil/teacher relationship that lasted until della Francesca’s death in 1492.

The influence of Pacioli and his mathematics was also felt by Leonardo –it was, in fact, fertile ground– and this is attested to by his notebooks which, during the period he worked with the Franciscan, are especially full of constructions with ruler and compass, and calculations and references to the secrets that could be achieved with them. Secrets among which the one dearest to da Vinci’s heart was to fly like a bird. “A bird is a machine that works according to the laws of mathematics,” he wrote in the Codex Atlanticus. “It is within man’s reach to reproduce this machine with all its movements, although not with the same strength… This machine built by man would only lack the spirit of the bird, and that is what man must imitate with his own spirit”.

References:

Antonio J. Durán, Pasiones, piojos, dioses… y matemáticas, Destino, 2009

Luca Pacioli, La divina proporción, Akal, Madrid, 1987

Seguramente Pacioli, maestro de Leonardo en la geometría sagrada platónica, colaboró activamente en estructuración geométrica del Cenacolo. Por ejemplo en la figura de Cristo se observa un triángulo equilátero, como la Tetraktys, que incluye un triángulo rectángulo de igual base cuyo ápice está en la joya del cuello, medio cuadrado, que en el hombre de Vitruvio corresponde a los genitales, quizás en relación a la cuadratura del círculo, que Leonardo creyó haber encontrado.

Por otra parte el Cenacolo es evidentemente una obra platónica inspirada en De amore commentarium in convivium platonis. Filosóficamente muestra la coincidencia del mensaje pagano (Simposio) con el cristiano, por ello en la triade a la derecha nuestra se observa el diálogo de Platón (tesis) con un teólogo cristiano (Dios es amor) y Ficino. El amor es el deseo de la belleza que se perfecciona en Dios, dice la segunda triade platónica.