In recent months, there has been a steady stream of disputes in Spain over the limits of freedom of speech. In April 2016, two puppeteers were directly imprisoned for several days on charges of glorifying terrorism, because one of their shows featured a character holding a banner reading “Gora Alka-Eta”. They were later tried and acquitted. The trials of Guillermo Zapata, a councillor on Madrid City Council, and the musician César Strawberry have also been notorious. Both were prosecuted for glorifying terrorism because of the tweets they had posted on social networks containing jokes and other witticisms about terrorist attacks or victims of terrorism. They were acquitted by the Audiencia Nacional, although last week the Supreme Court corrected Strawberry’s acquittal and sentenced him to one year in prison.

For me, these conflicts have a certain flavour of déjà vu. The surprising thing is that they remind me of one of the most bitter incidents in the life of Johannes Kepler, the mathematician, astronomer and astrologer who, at the beginning of the 17th century, in the midst of the scientific revolution , discovered the laws of planetary motion. Indeed, the scientific revolution, which transformed the way we explain the movement of stars and planets, contains magnificent examples of attacks on the most basic freedom of speech: what else was Galileo’s trial and condemnation at the hands of the Catholic Church for defending Copernicus’s theory that the Earth revolves around the Sun?

, discovered the laws of planetary motion. Indeed, the scientific revolution, which transformed the way we explain the movement of stars and planets, contains magnificent examples of attacks on the most basic freedom of speech: what else was Galileo’s trial and condemnation at the hands of the Catholic Church for defending Copernicus’s theory that the Earth revolves around the Sun?

But here I am interested in the Kepler affair, because it resembles, like two peas in a pod, what happened to the puppeteers.

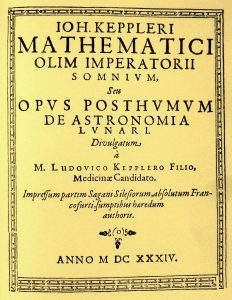

The issue was related to a novel entitled Somnium, which Kepler finished writing in 1608 – although it was published posthumously in 1634. In it, the protagonist reaches the Moon thanks to a magic spell from his mother and tells how the movements of the Earth were seen from there. Both Carl Sagan and Isaac Asimov agreed that Kepler’s novel was the first work of science fiction in history.

The fact was that this novel cost Kepler and, above all, his mother, Catherine Kepler, a serious trouble. She was accused of witchcraft and was, in fact, imprisoned in 1615 in a secular Protestant prison in Württemberg. Kepler’s novel had some autobiographical elements, so that the part of the plot in which the main character’s mother’s incantation is told was used as a piece of evidence in Kepler’s mother’s witchcraft trial. Kepler himself did his best to defend his then septuagenarian mother, and six years later succeeded in dismantling the accusation; but by then Catherine Kepler was broken by age, the year-long imprisonment and the psychological torture she suffered – where she was given vivid descriptions of the torments she would be subjected to if she did not confess – and died a few months later.

The present times bear little resemblance to the 17th century, one of the most ruthless eras of witch-hunting in Central Europe, when tens, if not hundreds, of thousands of innocent women were bludgeoned, tortured or burned in an orgy of blood and suffering caused by a devastating cocktail of religious intransigence, misogyny and superstition.

And while the puppeteers did not suffer physical torture during their days in jail, the fact that they were arrested for similar reasons to those for which Kepler’s mother was arrested, along with the Zapata and Strawberry trials – and the latter’s conviction – justify the unease that some of us citizens feel about the damage that the health of free speech seems to be suffering lately in our country.

This post participates in the 7.X Edition of the Carnaval de Matemáticas hosted by the IMUS Blog

References

A.J. Durán, El universo sobre nosotros, Crítica, Barcelona, 2015.

C. Sagan, Cosmos, Planeta, Barcelona, 1992.

Muy buena entrada

Por cierto, lo de Kepler como autor de la primera novela de ciencia ficción (o “viajes espaciales”) será con permiso de Luciano de Samósata.

Un saludo

Württemberg no es ninguna ciudad, sino el territorio, por aquel entonces, en donde ocurrió todo. A Katharina Kepler la encarcelaron en Leonberg, en esa zona, pero en 1620, y la ciudad de Lutero es Wittenberg, bastante lejos del resto.

En cualquier caso lo actual es lamentablemente cierto…

Corregido. Gracias Alberto.