Is there life in some other place in the universe? In some way, the Star Trek and Star Wars galactic sagas (begun in 1966 and 1977, respectively) have numbed the vertigo produced by such a fundamental question. The flood of issues that an affirmative answer to this question generates is colossal, starting with whether it will be intelligent life (whatever we can understand by intelligence) and ending with the anxiety of deciding to what extent a contact between the two worlds would not be disastrous for our way of life, or theirs, or both. The question of whether or not extraterrestrial life exists is several centuries old, dating back to the scientific revolution set in motion by Copernicus, which eventually equated the Earth with the planets, and the Sun with the other stars, thus making them all capable of hosting life. Throughout the 20th century it became a recurring theme in science fiction novels and films, most notably 2001: A Space Odyssey, which has just turned 50 and whose subsequent influence is hard to overstate. Given that this blog has a section called Kubrick’s Apes, it would be ungrateful not to dedicate at least one post to this landmark event.

I was able to watch the film for the first time in 1978, advised by a high school classmate who had an older brother with some film knowledge (he was the first guy to tell us about Woody Allen, Coppola, Scorsese… and Bo Derek, whom he told us he had once seen in person in Granada during the shooting of a film). I must remember that in 1978 there was no internet, no personal computers, not even videos or video clubs. Moreover, I lived in a village in the subbetic region of Córdoba, which was not exactly a hotbed of cultural interest, although two cinemas operated daily, and four in summer. The masterpiece we were supposed to view was long, very boring at times, especially during the episodes on the Discovery ship (detailed and cold, told with the same meticulous consistency of a documentary). Naturally I didn’t learn anything, and I ended up getting sick of the monolith (which in the refined pronunciation of my people sounds almost like “manolito”). But the sheer visual power of the images (enhanced by the music), and the sense that there was a coherent story behind the deliberate obscurity and histrionics that Kubrick had chosen to develop, made that first viewing of 2001: A Space Odyssey an unforgettable experience.

It took me a while to learn that the film’s screenplay had been turned into a novel by co-writer Arthur C. Clarke; in fact, the germ of the story came from a short story written by Clarke twenty years earlier, entitled “The Sentinel” (which was not the only element of the plot that came from other Clarke stories and novels). And it took me even longer to find a copy, which I bought in 1984 at an old book fair when I was already studying mathematics in Seville; a copy published in 1970 in the RTV collection of Salvat and Alianza, sponsored by the Francoist Ministry of Information and Tourism (“Collection unique in the world for its launch and print run, and which constitutes a decisive contribution to disseminating culture and promoting the world of books in Spain”, according to the credits page).

By then I had already seen the film a couple of times more, in the film club circuit that then worked so well in some faculties and technical schools of the University. Reading the novel confirmed for me that the composition of the story I had arrived at was essentially correct. I also realised that it was Kubrick’s approach and the magic of cinema, rather than the story itself, that had made 2001: A Space Odyssey a masterpiece (“It achieves a poetics comparable in stature to that of the great theogonies and cosmogonies of the old civilisations”, wrote the film critic Román Gubern).

The scientific coverage of the film was (almost) impeccable, as was that of the novel (don’t forget that Clarke was also an astrophysicist). Naturally there are many nods to astronomy, cosmology, artificial intelligence, and even mathematics. For example, Turing’s test of whether a machine is capable of thinking for itself is demonstrated several times with the HAL computer; in fact, both Turing and his test are explicitly mentioned in the novel, but not in the film. The novel also explicitly mentions “wormholes” (“worm bites”, according to Antonio Ribera’s translation for Salvat), as shortcuts to travel through the universe, recreated in the film in the long scene “The Stargate” (after HAL’s disconnection), where we travel through hallucinated, abstract and colourful landscapes, accompanied by György Ligeti’s contemporary music (which was used by Kubrick without the author’s permission). And there are even several nods to numerology (more explicit in the novel than in the film) when, for example, the preface comments on the (dubious) coincidence between the number of people who have passed through the planet and the number of stars in the Milky Way, one hundred billion in both cases; or when, towards the end, David Bowman realises the secret enclosed in the dimensions of the monolith: “How obvious, and how necessary, was that mathematical relationship of its sides, the quadratic series 1:4:9! And how naïve to have imagined that the series ended at that point, in only three dimensions”!

There is, however, one detail of the film (which is much more than a detail), and which I have never seen anyone give it the importance it deserves: despite being a science fiction film, and almost 90% of its footage takes place in spaceships, people in the film are constantly eating.

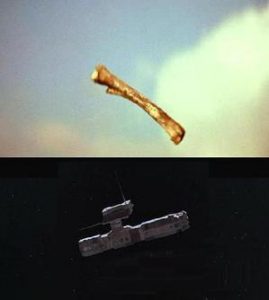

There is, however, one detail of the film (which is much more than a detail), and which I have never seen anyone give it the importance it deserves: despite being a science fiction film, and almost 90% of its footage takes place in spaceships, people in the film are constantly eating.  The monkeys are constantly foraging or devouring meat (and being devoured in turn), and the astronauts are repeatedly presented with meals that are as futuristic as they are unappetizing. And before passing on, the elderly Bowan is given the opportunity to enjoy the most decent meal in the whole film: the only meal, moreover, where there is wine; with its indefinable, faded greenish hue, it certainly doesn’t look like a great wine, but we mustn’t forget that Kubrick was an American, and Clarke an Englishman.

The monkeys are constantly foraging or devouring meat (and being devoured in turn), and the astronauts are repeatedly presented with meals that are as futuristic as they are unappetizing. And before passing on, the elderly Bowan is given the opportunity to enjoy the most decent meal in the whole film: the only meal, moreover, where there is wine; with its indefinable, faded greenish hue, it certainly doesn’t look like a great wine, but we mustn’t forget that Kubrick was an American, and Clarke an Englishman.

Leave a Reply