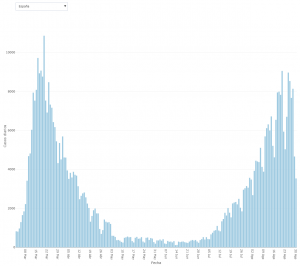

With great concern, we have been witnessing, almost since mid-July, how the number of those infected by COVID-19, as compiled by the Department of Health, has reached and even surpassed (in quite a few Autonomous Regions) the figures of the worst moments last spring, when the government had to confine us. Despite the fact that concern must be maintained because the epidemic is not evolving well in Spain, the situation cannot be compared with what happened in March and April. The reason is that the data on the number of infected people provides little information on its own about the real state of the pandemic and, if it is not placed in context, it can easily be misinterpreted. The number of infected persons detected essentially reflects the number of people who have tested positive for PCR (since 11 May the Ministry has also been counting positive for IgM). Due to its own idiosyncrasy, the number of infected people detected depends highly on various factors (administrative, management, protocol) unrelated to the evolution of the epidemic, which means that in different periods the same results have considerably different meanings. For example, in order to carry out PCR tests on the population, there must be enough tests, personnel to extract the samples and laboratories to process them; and all these parameters have changed a lot since March (we all remember the shortage of tests in Spain in March when the epidemic got out of control), so the capacity to carry out tests has increased by an order of magnitude if we compare it with what there was in March. But, perhaps even more importantly, the protocols for when and to whom a test should be done have also changed. In March, almost only patients who were already in a hospital and had symptoms compatible with COVID-19 were tested, and there was no subsequent tracing of possible cases close to those detected, nor were they tested if they were not hospitalized. After de-escalation, the tests are done in primary care and it is assumed that each positive case implies a tracking of the environment of the infected person and the realization of the corresponding tests to their contacts (hence the decrease, with respect to what happened in March and April, in the percentage of positivity of the tests, that is, the percentage of positives over the total number of tests performed). The consequence of these changes is that at the beginning of March only a small proportion of those actually infected were detected, whereas now a large proportion of the people actually infected are detected.

To get a better idea of the different situation between March and September, I’m going to make some simple statistical estimates; what’s important here is not so much the estimated number (probably not very accurate because of the simplicity of the technique I’ll use), but its order, because it will give a reasonable idea of how different the epidemic situation is now from what it was in March and April.

I will take the first data from the entry Sero-epidemiological study of the coronavirus, where, based on the serological report made by the Departments of Health and Science, I estimated that in the week from March 7 to 15 some 500,000 people were infected in Spain, while those detected were just over 7,000.

Let’s now try to estimate how many actual infections correspond to those detected in the week from August 29 to September 4. The number of actual infections in this epidemic is impossible to measure in real time by testing, but statistical estimates can be made using different types of data, such as the case fatality rate or data from serological surveys (see the entries How to estimate the actual number of infected by Covid-19? and Number of actual infected by Covid-19…). Here I will use a simple estimate of the actual number of infected from the lethality ratio; as I said before, it cannot be assumed to be very precise, but it will be more than enough to illustrate the huge difference with the situation in March.

To get an idea, the serological report of May established that, with a 0.95 probability, the coronavirus had infected between 2,200,000 and 2,500,000 people in Spain on May 1. If we take into account the average of 16 days between infection and death, and consider the 27,308 official deaths per covid-19 on 17 May, we find that the lethality ratio per covid-19 was between 0.0109 and 0.0124 in the first wave of the epidemic (until mid-May) (1.09 percent and 1.24 percent if we want to take this as a percentage).

Various circumstances indicate that the fatality rate must now be somewhat lower. Among these circumstances we can point out: (1) the ratio calculated for the first wave may be underestimated as some of the deaths were not counted at the most confusing times of the epidemic (remember that many of the deaths in nursing homes were not counted as covid-19 because very few or no PCR tests were done there); (2) we know that the lethality is considerably higher as the age of covid-19 patients increases, and it seems that in recent months the elderly are being considerably more careful than the young, which means a greater number of young people are actually infected than in the first wave; (3) nor is there now the hospital saturation that some regions suffered during the first wave and, furthermore, the accumulated experience has improved medical therapies against covid-19, so that the patients are treated more successfully, which means a decrease in deaths. We can therefore assume that the fatality rate is now lower than it was in Spring. For our calculations we are going to make three assumptions: 1% lethality, 0.75% and 0.5%.

According to the Department of Health, there were 256 deaths from COVID-19 in the 7 days prior to September 4th; if we subtract 16 days on average between infection and death, that gives us the following estimate for people who were infected between August 12th and 19th (according to the previous lethality ratios):

Lethality: 1% 0.75% 0.5%

Estimated actual infections 12-19 August: 25,600 34,133 51,200

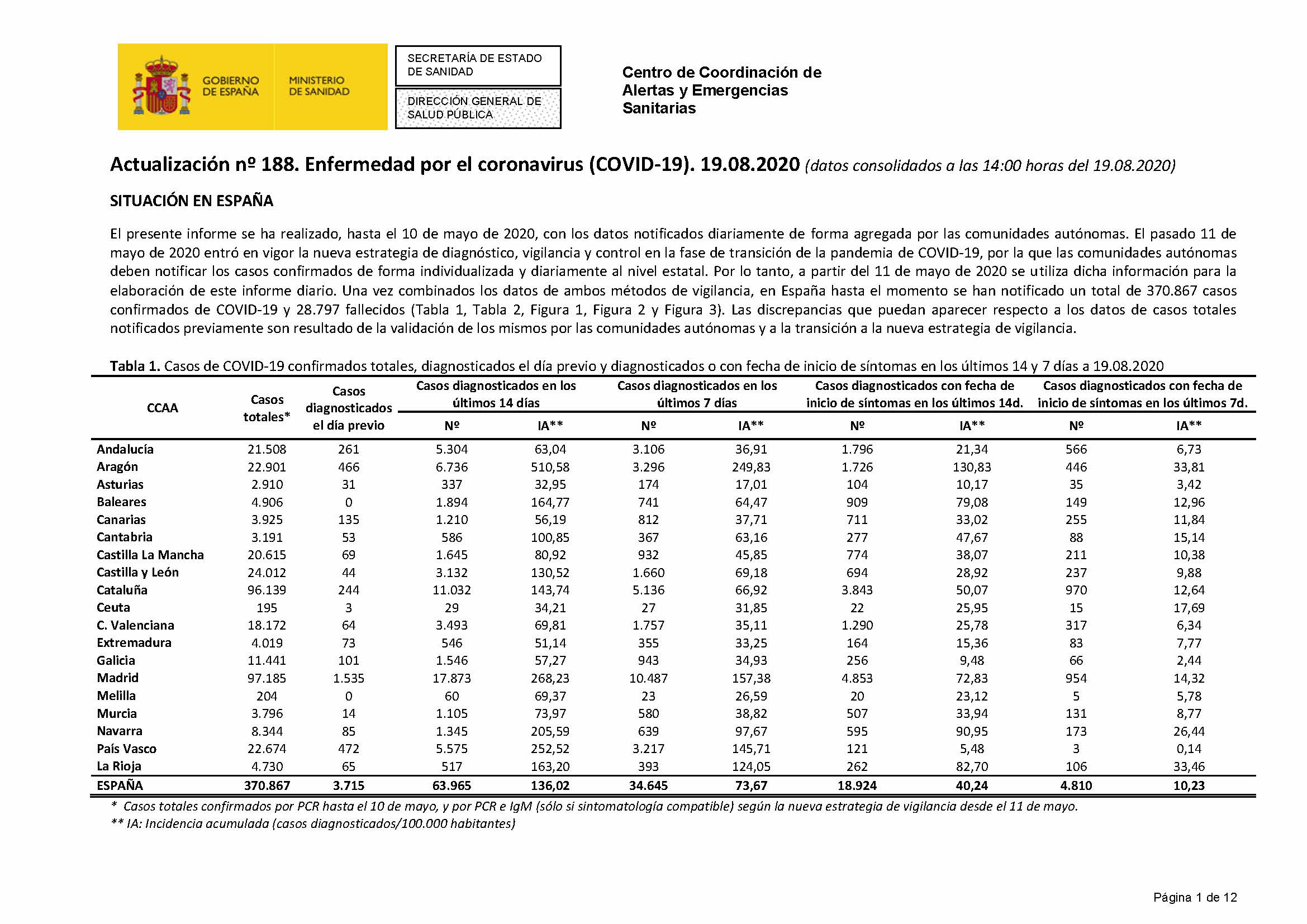

According to data collected by the Department of Health between August 12 and 19, 34,645 people were found to be infected.

Assuming the worst estimate (i.e. assuming that the lethality has fallen to just under half that of the first wave), 34,645 of the 51,200 infections were detected between 12 and 19 August. Compare now with the figures for the week between March 7 and 15 calculated earlier: just over 7,000 detected out of the half million infections that occurred during that week (although we have made the estimate for the whole of Spain, it should be pointed out that since July the epidemic has continued to show the great heterogeneity by province and region that it showed in the first wave of spring).

The above estimates show the huge difference from the current situation as compared to March, which forced confinement. We should not, however, be satisfied because the situation has worsened compared to June and because the epidemic exhibits here a worse evolution than in the European environment. In order to improve the situation, the public administrations must fine-tune the established protocols, which means strengthening primary healthcare, increasing and improving the efficiency of screening and, of course, ensuring better coordination between the different administrations (autonomous and central) and the different powers of the State (legislative, executive and judicial, so that judges do not have to overturn the rulers’ decisions). But citizens also have duties. In a previous entry (Confinement has saved hundreds of thousands of lives) I spoke of the spirit of early March: I am worried but unwilling to give up something, and that it seemed that this spirit was reviving in mid-June. As in the hardest stage of the confinement, it is time again to show that in this country adult and committed people are an overwhelming majority.

The above data for August and September are taken from the Department of Health website; specifically:

https://www.mscbs.gob.es/profesionales/saludPublica/ccayes/alertasActual/nCov/documentos/Actualizacion_188_COVID-19.pdf

https://www.mscbs.gob.es/profesionales/saludPublica/ccayes/alertasActual/nCov/documentos/Actualizacion_200_COVID-19.pdf

Llevando esas cuentas a sus últimas consecuencias, se puede ver que, de seguir la tendencia actual, tendríamos más de mil fallecidos al día para la última semana de octubre. Y no quiero pensar en el número de hospitalizados.

¿Habrá respiradores para todos los que lo necesiten? ¿Equipos para los sanitarios?

No es que sea fácil, pero utilizar las matemáticas y la estadística para esta situado, es el mejor sentido común que existe. Nos están vendiendo datos erróneos unos los estamos creyendo…. Desviando nuestra atención… Y no sé porqué