The preliminary report of the ENE-COVID19 sero-epidemiological study which has been carried out by the Spanish Department of Science and Innovation and the Spanish Department of Health since 27 April, was published on Wednesday. The study is based on the measurement of the prevalence of SARS-Cov2 infection (the coronavirus causing the Covid-19 epidemic) using (various types of) tests on a random sample of the population (more than 60,000 people).

This preliminary report places the confidence interval for the percentage of people actually infected by the coronavirus in Spain between 4.7% and 5.4% of the population, i.e., with a probability of 0.95, the number of people in Spain who have been infected by the coronavirus up to the beginning of May is between 2,200,000 and 2,500,000. I recall that the total number of infected detected up to 17 May is less than 280,000 (according to the official figures that the Department of Health has been collecting from the autonomous regions).

This study supports those of us who have been warning since the beginning of the epidemic that the number of people actually infected was possibly an order of magnitude higher than the number detected infected (see the entries How to estimate the number of people actually infected… and Number of people actually infected…).

If we take into account the evolution of the number of deaths, and that on average more than two weeks elapse between infection and death, if they occur, we can extrapolate these data to different dates, obtaining the following table (I have estimated the actual infected on day X taking into account the total number of deaths 16 days after day X and taking as a reference the figures of actual infected provided by the ENE-COVID19 report and the total deaths on 17 May).

Date Detected infected Estimate actual infected

7 march 525 185.000-213.000

15 march 7.928 680.000-780.000

31 march 95.923 1.530.000-1.765.000

15 april 180.659 1.990.000-2.290.000

1 may 242.979 2.200.000-2.500.000

Fortunately, the containment measures taken by the government since 15 March have been more in line with estimates of the number of people actually infected than with the number detected infected.

An aside: I have read and heard in several media that the Imperial College study at the end of March overestimated the number of people actually infected in Spain by putting it at around 7,000,000 people. This is not correct. Imperial College gave a statistical estimate of the number of infected; that is, its conclusion was not a number, but a set of numbers, each of which had a probability of corresponding to the actual number infected. Of these numbers, the one with the highest probability was 7,000,000, but this probability was not significant, not least because the confidence interval for the number of people actually infected in Spain in the Imperial College study gave a very wide range: between 1,800,000 and 19,000,000. The ENE-COVID19 study is also a statistical estimate, in this case with a much narrower confidence interval: 2,200,000 to 2,500,000. In my comments on this Blog to the Imperial College study, I was leaning towards the low end of their confidence interval. As the table above shows, one can conclude that the low end of the Imperial College study (1,800,000 actual infected at the end of March) is compatible with the high end of the confidence interval of the Science and Health Ministries’ ENE-COVID19 report (1,765,000 actual infected at the end of March, according to my extrapolation). Incidentally, the update of the Imperial College study gives a confidence interval for the percentage of people actually infected in Spain at the beginning of May of between 4.44% and 7.07% of the total population (compatible, therefore, with that given by the ENE-COVID19 report). It should be borne in mind that the methodology of both studies is completely different, with the ENE-COVID19 being much more reliable a priori as it is based on the sero-epidemiological study on a random sample of the population (while the Imperial College uses the evolution of the number of deaths).

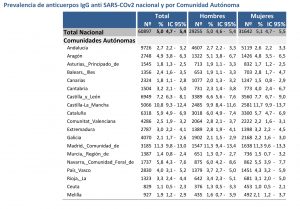

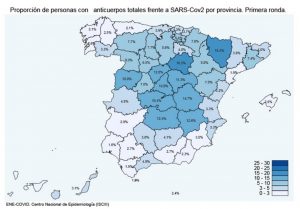

Another important conclusion of the ENE-COVID19 survey is the great heterogeneity of the epidemic in the different provinces and regions of Spain (2.7% of people actually infected in Seville differ greatly with a 12% in Madrid). This also proves right those of us who, since the beginning of the epidemic, have been insisting on this crucial fact, and the obvious consequence it implies: the containment measures should have been different in the different territories. This did not happen, although, at least, this is what is happening during the de-escalation. The ENE-COVID19 report suggests that Madrid acted as the main focus of the epidemic, something that has been confirmed by other studies (for example: in reference [1], see also this entry in Naukas, the Covid-19 mortality peak is correlated with the number of visitors per capita between Madrid and each province in the week before the containment was declared). With this scenario, the attitude of the President of the Community of Madrid accusing the central government of political reasons for delaying the de-escalation in Madrid is quite incomprehensible.

Several conclusions can be drawn from the preliminary results of the ENE-COVID19 study.

The first is that the containment measures were entirely necessary. Moreover, they have worked in containing an epidemic that had entered an exponential phase in early March.

The second is that the recommendations will have to be taken very seriously in order to avoid a resurgence. As I wrote in a previous post, whether there will be a new outbreak, or how long it will take and how serious it will be, will depend not only on whether the government gets the measures right, but also on how responsibly citizens behave and the habits they adopt.

And the third is that it will be necessary to maximise the capacity for early detection of the outbreak, through rapid tests in primary care centres, but also by making reliable estimates of the number of people actually infected and quarantining not only those who have been confirmed infected, but also the number of infected detected, because otherwise the outbreak could be as sudden as this first outbreak has been. On 7 March, with 525 infected detected, few, if anyone, thought that the epidemic was in full exponential process and would force the population into confinement just eight days later. The situation would have been different if we had been able to estimate that the actual number of infected was already around 200,000.

References

[1] Mattia Mazzoli, David Mateo, Alberto Hernando, Sandro Meloni, Jose Javier Ramasco (2020) «Effects of mobility and multi-seeding on the propagation of the COVID-19 in Spain» MedRxiv DOI:10.1101/2020.05.09.20096339

¿Se sabe a ciencia cierta la fiabilidad de los tests que han servido para hacer este estudio? Creo que se ha hecho con los tests rápidos que compró el gobierno y cuya fiabilidad fue bastante cuestionada. Si se han usado “varios tipos de tests” serán de distintos tipos de fabricantes, pero no PCR, por lo que he leído en otros foros donde al menos una doctora, implicada en la captura de datos, explicaba lo que sabía del asunto.

¿Cómo influye esa fiabilidad de los tests en la validez del estudio?

He leído que según la fórmula de Bayes, la probabilidad de que un paciente al que le da un resultado positivo en un test de COVID-19 tenga realmente el virus es de alrededor del 8%, si se dan las siguientes premisas:

la prueba tiene una fiabilidad del 80%, un índice de falsos positivos del 9,6% y se sabe (por otras pruebas más fiables) que en la población del país (el que sea) existe un 1% de infectados de COVID en ese momento.

¡Un 8% de probabilidad! Cuando cualquier lego (e incluso la mayoría de los médicos) la habría estimado en un prudente 75% (algo menos de la fiabilidad de la prueba) o, por lo menos, superior al 50%.

¿Qué nos dice esto de la fiabilidad global del estudio hecho por el gobierno?