The manufacture of the first atomic bombs during the Second World War was a turning point in history, where science and technology had to fight in the ring of ethics. And mathematics was also involved. Think of the Los Alamos laboratory, where the design and assembly of the bombs took place. There were mostly engineers and nuclear physicists, but also chemists and a handful of mathematicians.

The mathematicians were mostly involved in estimating, approximate resolution of the very complicated equations that were used to anticipate what the explosion would be like depending on the design of the bomb, and so on.

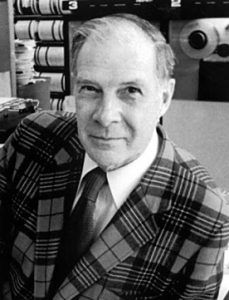

One of the high points came when someone once raised the question of whether an atomic explosion would not release enough neutrons to cause a chain reaction in the gases in the atmosphere. The mathematicians were given the job of estimating whether that could actually happen. Richard Hamming (1915-1998) was one of them.

Hamming himself recounted the event in horrifying detail: “Shortly before the test bomb went off – it should be borne in mind that a smaller-scale experiment could not be done, because you either reached critical mass or there was no explosion – someone asked me to check some accounts he had made; I said yes, thinking of passing them on to a subordinate. When I asked him what they were, he replied: “It’s the probability that the test bomb will blow up the whole atmosphere as well”. I decided then that I would check them myself! The next day, when he came to see me, I said, “The maths is apparently OK, although I don’t know the value of the section within which the oxygen and nitrogen nuclei capture neutrons” – there were no experiments done at those energy levels. He replied as a physicist replies to a mathematician, “It’s the maths I want you to check, not the physics”, and he went away. Then I said to myself, “What are you doing here, Hamming, involved in a matter that will risk all known life in the universe and not knowing some of the essentials?” I was pacing up and down the corridor when a friend asked me what I was worried about.

Hamming himself recounted the event in horrifying detail: “Shortly before the test bomb went off – it should be borne in mind that a smaller-scale experiment could not be done, because you either reached critical mass or there was no explosion – someone asked me to check some accounts he had made; I said yes, thinking of passing them on to a subordinate. When I asked him what they were, he replied: “It’s the probability that the test bomb will blow up the whole atmosphere as well”. I decided then that I would check them myself! The next day, when he came to see me, I said, “The maths is apparently OK, although I don’t know the value of the section within which the oxygen and nitrogen nuclei capture neutrons” – there were no experiments done at those energy levels. He replied as a physicist replies to a mathematician, “It’s the maths I want you to check, not the physics”, and he went away. Then I said to myself, “What are you doing here, Hamming, involved in a matter that will risk all known life in the universe and not knowing some of the essentials?” I was pacing up and down the corridor when a friend asked me what I was worried about.  I told him so and he replied: ‘Don’t worry, Hamming, no one will ever accuse you of anything’. That was the way it was: we entrusted all the life we know about in the known universe to a few accounts. Mathematics is not merely an idle art form but an essential part of our society”. The calculations proved correct, and the atmosphere did not explode at the same time as the first atomic bomb exploded in the Alamogordo desert on 16 July 1945 (photo).

I told him so and he replied: ‘Don’t worry, Hamming, no one will ever accuse you of anything’. That was the way it was: we entrusted all the life we know about in the known universe to a few accounts. Mathematics is not merely an idle art form but an essential part of our society”. The calculations proved correct, and the atmosphere did not explode at the same time as the first atomic bomb exploded in the Alamogordo desert on 16 July 1945 (photo).

His experience at Los Alamos probably made Hamming a skeptic of some mathematical sophistications. For example, he found the Lebesgue integral unnecessary for describing physical reality, and he explained this quite forcefully in a famous quote: “Does anyone really believe that the difference between the Lebesgue integral and the Riemann integral can have physical relevance, say, so that the flight of an aeroplane depends on that difference? Well, even if someone says it does, I wouldn’t mind flying in that plane”.

To Hamming we owe a code for detecting errors in the transmission of numerical data that gave him a certain celebrity and from which, in a way, the check digits used today in bank accounts derive.

References

- R.W. Hamming, Mathematics on a Distant Planet, The American Mathematical Monthly, 105, 640-650, 1998.

- A.J. Durán, Pasiones, piojos, dioses… y matemáticas, Destino, Barcelona, 2009.

This post participates in Edition 7.7 of the Carnaval de Matemáticas, organised this time by Los Matemáticos no son gente seria (Mathematicians aren’t serious people).

Leave a Reply