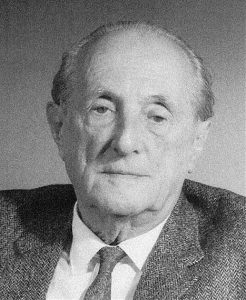

Over the next few months we will be devoting some Fun & Games to the book One hundred problems in elementary Mathematics, by the Polish mathematician Hugo Steinhaus (1887-1972). Together with his colleague Stefan Banach, Steinhaus founded a strong mathematical analysis group at the University of Lwów, which used to hold mathematical gatherings in the Scottish Café in Lwów. The history of the gatherings, including their mathematical significance and the disasters that befell their participants during the Second World War, especially during the Nazi occupation, is fascinating – and not very well known. It shows, as few others do, the extent to which mathematics is no stranger to historical upheavals. So we will devote half a dozen entries in Basic wardrobe to the Scottish Café chat room, making them coincide with the Divertimentos of Steinhaus’s book – those interested readers who want to get a head start on this narrative in instalments can find the full story in chapter 3 of my book Pasiones, piojos, dioses… y matemáticas, Destino, 2009.

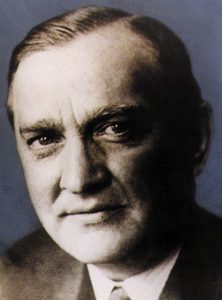

Today’s entry will be devoted to outlining the biographical profiles of Steinhaus and Banach.

Steinhaus studied mathematics in Göttingen between 1906 and 1911, where he obtained his PhD under the supervision of David Hilbert. Studying abroad was to some extent commonplace in Poland, which was then divided between Russia, Prussia and the Austro-Hungarian Empire. After the end of the World War I, Poland was once again a free country, and Steinhaus ended up as a professor in Lwów. Steinhaus lived in Lwów until the city was taken over by the Nazis in 1941.

Banach was born in Kraków in 1892. His father’s name was Stefan Greczek, although Banach preferred to use his mother’s surname, or at least the one recorded for her on his birth certificate: “son of Katarzyna Banach”. His mother abandoned him a few days after his birth; she was never married to Banach’s father and little is known about her – actually, nothing at all: no matter how hard her son tried to find out, she was pure mystery. Banach was raised by his paternal grandmother in Ostrowsko, a small village 80 km south of Kraków, hidden in the Carpathian Mountains.

Steinhaus used to say that his best mathematical discovery was Banach, whom he had met by chance in Kraków in 1916.

Like Steinhaus, Banach ended up as a professor in Lwów (1922), and there they founded a strong mathematical analysis group. On Saturday afternoons they used to meet in a classroom at the University – Saturdays were then school days; the peculiarity was that the most fruitful part of these meetings took place, not at the University, but in some cafés in the neighbourhood, where the mathematical discussion usually went on for several hours longer. In the systematic use of cafés as a scientific refuge, Banach’s mark can be seen, because there were few things that Banach liked as much as doing mathematics in a café. Two of them were particularly dear to him, the Roma and the Szkocka; “szkocka” happens to be Polish for “Scottish”. At one point, Banach had a friction with the owners of the Café Roma, where he used to spend much of his time – especially in the last days of the month before he got his salary – and it seems that there were complaints about late payment for drinks, and therefore much of the group settled down at the nearby Scottish Café.

The Scottish Café was attended by professors of long standing, such as Antoni Łomicki, who for a certain period was Director of the Institute of Mathematics at the University and to whom Banach, who had just arrived in Lwów, was an assistant, Włodzimierz Stożėk, who was Dean of the Faculty of Mathematics, not to mention Hugo Steinhaus, Stanisław Ruziewicz, and, of course, Banach himself; but also young people who were just starting their mathematical careers at that time, such as Herman Auerbach, who was a chess enthusiast, Feliks Barański, Mark Kac, or Stanisław Ulam; and also others in between: Stefan Kaczmarz, Stanisław Mazur, Władyslaw Orlicz, Juliusz Schauder, or Stanisław Saks. Almost all of them have given their names to methods, concepts, theorems and results. In the case of Banach, and to a lesser extent also in the case of Steinhaus and others, their name has become a frequent adjective in the vast toponymy of mathematics.

Not many of them survived the disasters of World War II.

Steinhaus did, so he had to live in hiding during the war under a false identity, as he would have been condemned by the Nazis for his Jewish ancestry. After World War II, Lwów changed its name to L’viv and became part of Ukraine. An ethnic cleansing then took place, which brought to Wroclaw Steinhaus and the mathematicians from Lwów who survived the war; it so happened that Wroclaw had also changed country after the Second World War: it had previously been part of Germany and was called Breslau – there, in fact, Felix Hausdorff had been born in 1868. Steinhaus died in 1972.

Banach was feeding lice for much of the Nazi occupation and narrowly survived the war: he died of lung cancer on 31 August 1945; Banach’s burial in Lwów was turned into a patriotic act by the Poles still living there – though this may be nothing more than legend.

References

A.J. Durán, Pasiones, piojos, dioses… y matemáticas, Destino, Barcelona, 2009.

Encuentro muy interesantes estas reseñas biográficas de estos grandes matemáticos. Quizá es porque me permiten percibirlos como seres de carne y hueso.