In the next post of Fun & Games we return to the book One hundred problems in elementary Mathematics, by the Polish mathematician Hugo Steinhaus (1887-1972). So today we will dedicate this entry to continue with the stories of the Scottish Café (for the first three see Stories of the Scottish Café: 1. Steinhaus and Banach, Stories of the Scottish Café: 2. The Mathematical Gathering, Stories of the Scottish Café: 3. The Scottish Notebook).

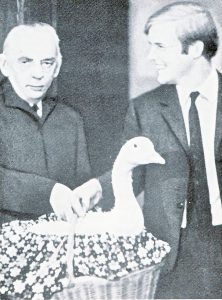

There is something very sweet and touching in the stories of the Scottish Café; in particular in almost everything about the Scottish Café Notebook. From its instructions for use: ‘The Notebook was kept in the Scottish Café by a waiter,’ wrote Ulam in his memoirs, ‘who knew well the ritual. When Banach or Mazur arrived, it was enough to say to him ‘please, the notebook’, so that he could take it along with the coffees”; up to the prizes offered by some proponents to whoever was able to solve the problems they posed. Some are decidedly modest: “A bottle of wine”, or “two”, “a small beer”, or “two” or “five”, while others are more sophisticated: problem 162, proposed by Steinhaus, offers whoever solves it “a dinner at the George”; the George was a hotel in Lwów where from time to time the students of the University held dances – they used to invite Banach, whom they appreciated very much and who was, moreover, an excellent dancer. The 153rd problem of the Notebook was proposed by Stanisław Mazur on 6 November 1936 and offered as a prize “a live goose”; thirty-six years later,  that is, in 1972, Per Enflö solved the problem and, naturally, received from Mazur a live goose lovingly packed in a basket. The mother of Przemysław Wojtaszczyk, then a young Polish mathematician, then slit the goose’s throat and prepared a superb meal with it.

that is, in 1972, Per Enflö solved the problem and, naturally, received from Mazur a live goose lovingly packed in a basket. The mother of Przemysław Wojtaszczyk, then a young Polish mathematician, then slit the goose’s throat and prepared a superb meal with it.

There are some problems that include a variety of prizes and detailed instructions for awarding them: “For the calculation of the frequency: 100 grams of caviar. For proof that the frequency exists: a small beer. For a counterexample: a cup of coffee”. Others illustrate the occasional participation of foreign mathematicians in Scottish Café gatherings: “a fondue in Geneva”, or “a meal at the Dorothy in Cambridge”. Perhaps some of the prizes admit subtle and even equivocal interpretations: there is the “bottle of positive-measure whiskey” offered by John von Neumann on 4 July 1937 – perhaps revealing one of the great Hungarian mathematician’s hobbies – or the “a kilo of bacon” offered by one of the Jewish members of the gathering, Saks, on 8 February 1940 – perhaps betraying a food shortage at the beginning of the war; Others, however, have an unmistakable interpretation, though not so much because of what was being offered – “a bottle of wine”, “a bottle of champagne” – but because of who was offering it: Russian mathematicians, who were ever-present at the get-together from the end of 1939 until May 1941, during which time Lwów was occupied by the Soviets after the partition of Poland agreed by Hitler and Stalin at the beginning of the Second World War.

In the summer of 1939, Stanisław Ulam took part for the last time in the Scottish Café discussion group; he himself admits that he thought, somewhat naively, that there would be no war, although others were more realistic. One of them was Stanisław Mazur. Convinced that a great war was imminent, and aware of the mathematical importance the notebook had acquired over the years, Mazur had devised a plan to protect it – a plan whose naivety, when compared to the savage times ahead, is even painful: “Mazur told me that our results must not be lost,” wrote Ulam; “he explained that as soon as the war started, he would hide the notebook in a small box, which he would bury somewhere where it could be found later. Specifically, near the post of one of the goals on a nearby football field”.

We do not know whether Mazur put his plan into practice, but the Scottish Notebook survived the war. After Banach’s death in 1945, his son found it – it is still in his possession today – and sent it to Steinhaus who copied it by hand and, years later, sent it back to Los Alamos to Ulam, with the consequences that I discussed in the entry Stories of the Scottish Café: 3. The Scottish Notebook.

After the Ribbentrop-Molotov Agreement in August 1939 and the subsequent partition of Poland, things began to change in Lwów. After being occupied by the Russians, Banach’s prestige among Soviet mathematicians preserved the mathematical gathering at the Scottish Café; the University changed its name and Ukrainian professors were brought in from Kiev and Kharkov, but Banach was appointed Dean of the Faculty of Physics and Mathematics, as well as Head of the Department of Mathematical Analysis and, later, Councillor of the City Council. Banach travelled several times to Moscow to meet Russian mathematicians of the stature of Alexandrov and Sobolev, who, in turn, visited Lwów, participated in the café’s social meetings and left their mark in the form of several problems included in the Scottish Notebook.

The last problem in the Notebook, dated 31 May 1941, was proposed by our Steinhaus; it is difficult to know what it refers to, but one can venture the following. It was not unusual at that time for a smoker to carry two boxes of matches with him: the problem possibly proposes to study the statistical distribution of the number of matches remaining in one box just as the last match is taken from the other. But perhaps the most interesting thing about this problem is precisely the cryptic and hurried way in which it is written, because it is the unmistakable sign that tragedy had already begun to strike the protagonists of these little stories.

References

- A.J. Durán, Pasiones, piojos, dioses… y matemáticas, Destino, Barcelona, 2009.

- Ulam, Adventures of a mathematician, University of California Press, Berkeley, 1991.

Leave a Reply