A few weeks ago I devoted a post (Pacioli and Leonardo) to the personality of Luca Pacioli, taking as an excuse the fifth centenary of his death. There I commented on his relationship with Leonardo da Vinci. This entry will be devoted to his more than likely influence on Albert Dürer.

Of all Renaissance artists, it was perhaps Dürer who had the greatest mathematical knowledge. This knowledge, which covered the fortification of cities and fortresses, the use of the compass and square to measure solid bodies, the study of human proportion and the geometric design of the alphabet, was written down by Dürer at the end of his life in various works, most of which did not see the light of print until after his death.

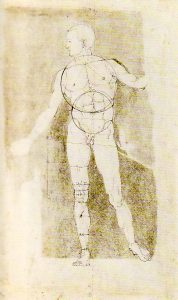

Much of his mathematical knowledge was acquired during his two visits to Italy. The first took place in 1494-5. Jacopo de Barbari –to whom some attribute the famous portrait of Luca Pacioli– led him to consider the problem of proportion, particularly in order to achieve the beauty of the classical canon in the representation of the human body, using symmetry and metric relationships between the parts of the body. But Barbari refused to let him know the optimum proportions for drawing the human body – keeping the formulas to oneself was to some extent common at the time; think of the Italian algebraists and the formulas for solving the equations of the third and fourth degrees. Dürer came to the conclusion that the classical nude depended on a secret formula –the “secretissima scientia”– and set out to discover it. To this end he turned to Vitruvius –whom he read in 1500– and his canon, and studied classical sculpture. He also tried to systematise posture and proportions by means of constructions with ruler and compass. Figures survive from 1500 and 1504 in which he used geometric proportions to determine measurements, as well as posture and contours, which he constructed with arches drawn with a compass. However, something did not quite work, and the figures seem to violate nature, hardening with geometric curves what should have been organic undulations.

His second visit to Italy (1505-1506) was even more decisive. Among other cities, Dürer visited Bologna in 1506 and there he was instructed in the “secretissima scientia” by a master whose name he did not reveal, although many have believed that they recognise Luca Pacioli himself in this anonymous figure.

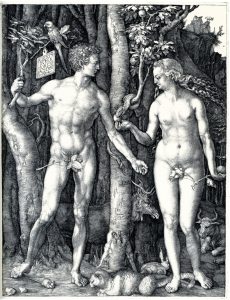

The extent to which the “secretissima scientia”, behind which lies the golden ratio –among other relevant ratios– as an unknown formula for the construction of a perfect canon for the human body, ceased to be secret for Dürer, is fully demonstrated by his magnificent nudes of Adam and Eve in the Prado, and by his preparatory sketches. In them, Dürer improved the proportions and added straight lines to the arcs of circumference: this helped him to fix the poses and proportions, but not the contours, which now appear more fluid and softer. He moved from the eight-headed canon, learned from Vitruvius, to a nine-headed canon, which makes his figures more slender.

The difference between having this secret knowledge and not is the difference between the appearance of our first parents, slightly big-headed Adam and slightly chubby Eve, in the engravings that Dürer produced in 1504 –today in the Albertina in Vienna– and the glorious slenderness of the first couple in the oil paintings that Dürer executed in 1507 -today in the Prado Museum-.

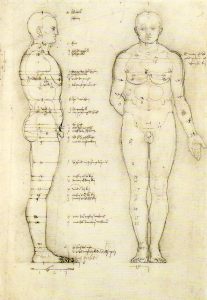

After his trips to Italy, Dürer further pursued the study of proportion.  To improve his knowledge of proportions, he made a large number of studies and measurements of living models, combining average values of the limbs and especially beautiful body parts to obtain the most perfect possible type. He noted these values with fractions on the body prototypes and distinguished them according to physical constitution. All this resulted in a profuse collection and elaboration of data that was finally transferred to the canvas. This use of mathematics was unique in the natural sciences of his time.

To improve his knowledge of proportions, he made a large number of studies and measurements of living models, combining average values of the limbs and especially beautiful body parts to obtain the most perfect possible type. He noted these values with fractions on the body prototypes and distinguished them according to physical constitution. All this resulted in a profuse collection and elaboration of data that was finally transferred to the canvas. This use of mathematics was unique in the natural sciences of his time.

References:

Durero. Obras maestras de la Albertina. Catalogue of the exhibition. Museo del Prado. 2005.

Antonio J. Durán, Pasiones, piojos, dioses… y matemáticas, Destino, 2009

Un gusto haber encontrado este blog….uscando bocetos de Durero. gracias por difundir generosamente, estoy preperando una clase y citare esta fuente. Desde Argentina saluda atte. Mir Lusewix