In the next post of Fun & Games we return to the book One hundred problems in elementary Mathematics, by the Polish mathematician Hugo Steinhaus (1887-1972). So today we will dedicate this post to the last story of the Scottish Café (for the first five see Stories of the Scottish Café: 1. Steinhaus and Banach, Stories of the Scottish Café: 2. The Mathematical Gathering, Stories of the Scottish Café: 3. The Scottish Notebook, Stories of the Scottish Café: 4. The Scottish Notebook Awards and Stories of the Scottish Café: 5. Wartime Gatherings).

In 1909, Charles Nicolle of the Pasteur Institute in Paris discovered that lice are responsible for transmitting the pathogenic agent of typhus. The high mortality of one of its variants, Epidemic typhus, also known as louse-borne typhus, has been one of the plagues of mankind, especially in times of war. The great plague that decimated the Athens of Pericles, and killed him, is said to have been caused by this variety, as was the epidemics that coincided with the conquest of Granada, the retreat of the Napoleonic armies from Russia, and the two world wars of the 20th century.

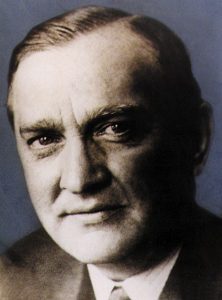

Shortly before World War II, Rudolf Weigl (1883-1957) succeeded in developing an effective typhus vaccine in his laboratory at the University of Lwów. The discovery was of major epidemiological importance, and several million people were vaccinated during the German occupation of Poland; later it was also used in China, Ethiopia and other countries.

The importance of Weigl’s typhus research in Lwów allowed him some privileges during the war. First, under Soviet occupation at the beginning of the war. Nikita Khrushchev, then First Secretary of the Communist Party of Ukraine and later of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (1953-1964), offered Weigl the title of Academician and the direction of a bacteriological institute in Moscow to develop his vaccine. Weigl must have been a very persuasive character because, even though he refused the offer, he not only avoided the foreseeable reprisals but also got Soviet support to expand his Institute in Lwów and, furthermore, managed to keep his staff out of the deportations to Siberia. Something similar happened under German occupation. As described by Waclaw Szybalski, the son of a close associate of Weigl’s who emigrated to the United States and became an oncologist at the University of Wisconsin: “The Nazis gave Weigl permission to have a radio […] This was a blessing, since being caught with a radio was punishable by death. Weigl was very courageous and cooperated with the Polish resistance during the Nazi occupation. Several shipments of his vaccine ended up arriving illegally in the Warsaw ghetto – some transported by my father and me – and in other Jewish ghettos in large cities, where typhus had reached epidemic proportions”. Władysław Szpilman, whose story of survival in the Warsaw ghetto was made into a masterpiece by Roman Polansky in the film The Pianist, recounted that Dr Weigl was as famous in the ghetto as Hitler, though for quite different reasons.

In order to prepare the vaccine, Professor Weigl needed to breed a huge number of lice. But lice only survive if they feed on human blood.

The German invasion of the USSR caught Banach in Kiev; despite the foreseeable repressions that awaited him in Lwów because of his friendly relationship with the Soviets, Banach was able to catch the last train and return to his hometown: there was his wife, his son, as well as his father and a half-brother, who had taken refuge in Lwów before Kraków, where they lived, fell into the hands of the Nazi forces. Banach was arrested by the Gestapo but released a few weeks later. From autumn 1941 until the end of the German occupation in July 1944, Banach was one of the privileged few who volunteered to feed lice with his own blood at the Weigl Bacteriological Institute. This led to considerable physical degradation. A colleague’s wife describes him in those years as “an exhausted, hungry and gloomy man, although before the war he had been of a very robust build”.

As I have just written, getting a job as a lice nurser was a privilege: “‘During the Nazi occupation,” wrote Szybalski, “being employed at the Weigl Institute granted a certain degree of protection against arbitrary arrest and deportation to Nazi concentration camps. The Gestapo preferred to avoid dealing with people who might accidentally infect them with typhus: it was well known that those of us who worked at the Institute could be infected with lice. Moreover, we employees wore a clearly visible identification issued by the Office of the Commander-in-Chief of the German Army. This “Ausweiss” was another of Weigl’s inventions that provided us with security […] In this way, Weigl helped many of the then unemployed professors of the University by employing them as lice feeders. Such employment entailed special food rations, and lessened the possibility of arrest, deportation and/or death during German occupation”.

Among those privileged were many of Lwów’s intellectuals, including the university professors – Banach, Orlicz and other mathematicians among them. The Nazis were determined to reduce Poland to a nation of slaves, so they banned university education in the country, leaving only a few technological facilities for their own use. Polish universities, however, achieved a certain degree of clandestine operation. The lice feeders at Professor Weigl’s Institute facilitated the covert operation of the University of Lwów: “‘Since the feeding of lice occupied the feeders for only one hour a day,” Szybalski explained, “[…] the feeders had plenty of time to organise clandestine university courses and to carry out other educational and patriotic activities.

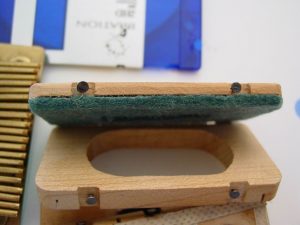

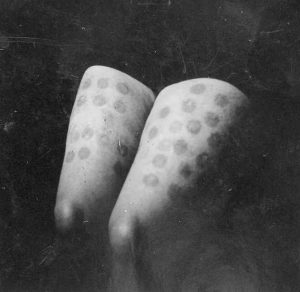

For the breeding and feeding of the lice, Weigl had invented an ingenious system. It consisted of small wooden boxes -\(4\times 7 \times 1\) cm – sealed with paraffin to prevent the insects from escaping; one of their sides, protected by a small lid, was made of a very fine mesh that only allowed the lice to stick their heads out to feed. Between 400 and 800 larvae were deposited in these boxes, along with woollen threads for the eggs to lay when they grew. Between 7 and 11 of these boxes were placed on the legs of the feeders, held in place with an elastic band and with the lid open; according to Szybalski: “Men usually placed the boxes on their calves, but women preferred to place them on their thighs, to hide under their skirts the reddish marks left. After a feeding session of 30 to 45 minutes, not only the louse’s intestines, but its entire body looked like a balloon, as each insect ingested a quantity of blood equal to its weight”.

In the introduction to this blog it is mentioned that in mathematics there is a permanent conflict between prudence and passion; a passion that is very similar to the creative fever that occurs in artists, be they painters, composers or poets. There are many people who believe that mathematics is something so cold that it cannot generate any kind of passion. Not true: what, if not the most rapturous of passions, can make people forget that they have a few thousand lice attached to their calf sucking their blood?: “I had to supervise a breeding unit whose feeders were almost all mathematicians from the famous Lwów School, including the world-famous Professor Stefan Banach,” wrote Szybalski, “[…] It was intellectually very stimulating, if also somewhat surreal, to listen to them discussing the frontiers of mathematics, topology and number theory, while they were feeding lice. Moreover, I had to be very scrupulous with them in keeping track of time, because in the fervour of their discussions they would keep the little boxes attached to their legs for more than 45 minutes, overfeeding the lice. This had terrible consequences, because our laboratory lice had lost their natural instinct to stop eating, and continued to suck their blood until the sheer quantity they stored in their intestines caused them to burst”.

References

A.J. Durán, Pasiones, piojos, dioses… y matemáticas, Destino, Barcelona, 2009.

Leave a Reply