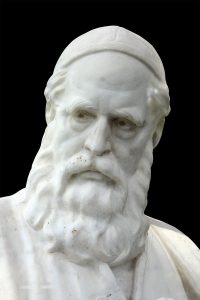

Omar Khayyam (1048-1131) was a mathematician, astronomer, philosopher and poet; we have already dedicated an entry in this blog to his poetic compositions, the rubaiyat, Rubayat of Omar Jayyam. Here we will explore his relationship with the “assassins”.

Shortly after Khayyam’s death, a haunting legend developed that establishes links of scholarly friendship between him, Nizam el-Molk and Hassan ibn Sabbah, three of the most interesting characters in medieval Iranian history. Nizam el-Molk was vizier to the Seljuk Sultan Alp-Arslan (1029-1072) and, after his death, to his son Malik Shah (1055-1092) – under whom the Seljuks reached their apogee, ruling over Iran, the northern half of Afghanistan and much of Central Asia, Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Palestine and Anatolia.

In turn, Hassan ibn Sabbah was the founder of the “hashshashin”, or “hashish-eaters”, a commune of fanatics belonging to the Shiite sect of the Nizaris who, from their unyielding stronghold of Alamut in the Elburz Mountains south of the Caspian Sea, elevated murder, sometimes selective and sometimes indiscriminate, to the rank of one of the fine arts, as the heterodox Thomas de Quincey would have said. Precisely from the word “hashshashin” etymologically derives the name by which in most Western languages a person who kills another with premeditation and malice aforethought is designated: “asesino” in Spanish, “assasin” in French and English, or “assasino” in Italian – Dante was, in his Divine Comedy, one of the authors who first used the term and helped to spread it throughout the Western world.

But both the real dimension of the assassins’ sect and that of its creator have been half obscured by the fumes of their own legend. Rather than a sect, the “Hashshashin”, or the Nizarids, as it would be more accurate to call them, were a faction that emerged in the umpteenth schism suffered by the Shiites. The Nizarids played an important role in the power-sharing and religious and political tensions between the various factions of Islam during the 11th, 12th and 13th centuries.

From their impenetrable fortresses, of which the castle of Alamut was the flagship, they came to dominate large parts of Syria and Iran, and their influence did not cease until the Mongol conquests of the mid-13th century.

The legend of the assassins and their leader, the ineffable “Old Man of the Mountain”, was first forged by the Crusaders, and finally chiselled by Marco Polo. The Venetian attributed the fanaticism and loyalty of the assassins to the “Old Man of the Mountain” to the fact that the latter intoxicated them with hashish – hence the name “hashshashin” – and took them to a garden populated by Huris: “There resided the most beautiful ladies and maidens in the world,” we read in The Book of Wonders, “who could play all instruments very well, sing melodiously, dance around cool and shady fountains better than any other woman, and, above all, were well instructed in making men unimaginable caresses and confidences”. Mesmerised by this foretaste of what Muhammad had promised to his most faithful believers, “the old man has inspired his people with such a desire to die in order to go to paradise,” I continue quoting Marco Polo, “that whom he commands to go and die in his name considers himself very fortunate in the certainty and reward of such a prize”.

The psychology of those “hashshashin” is not much different from that of today’s Islamic terrorists, be they Palestinian suicide bombers, Iraqi suicide bombers, al-Qaeda, ISIS or some other of its variants – though one could also mention the kamikazes, who blossomed in the heat of Japanese imperialism.

The legend of Omar, Nizam and Hassan tells how the three of them met at a school in Nishapur and became close friends. “Following the tradition of the young men of their time,” reads a 14th century Arabic manuscript now in the British Museum, “the three comrades culminated their friendship with a rite in which, after marking their lips with each other’s blood, they solemnly swore that any one of them who attained high rank would favour the other two friends with his power”. Thus, when Nizam el-Molk attained the glory of being grand vizier of the Seljuk sultans, Omar and Hassan reminded him of their blood oath, and Nizam offered them both the government of a province. Omar refused: “For being an eminent philosopher, astrologer and mathematician,” I continue quoting from the Arabic manuscript in the British Museum, “he did not desire the government of any province, nor did he wish to encumber the people with commands and prohibitions. “I prefer,” he told the grand vizier, “that you assign me a stipend or a pension” – it is understood, so that he could devote himself to science, philosophy and poetry. Hassan also refused his old friend’s offer, but for a different reason: he thought Nizam’s offer was too little. Thus the friendship between Hassan ibn Sabbah and Nizam el-Molk was broken, and they became hopeless enemies. When Hassan ibn Sabbah created the sect of assassins, one of his first victims was Nizam el-Molk, who was stabbed by one of Hassan’s henchmen in 1092.

The legend, though much repeated, is most likely fabricated, for since the late 19th century the birth and death dates of the three supposed friends are reasonably well established: 1018-1092 for Nizam, 1034-1124 for Hassan and 1048-1131 for Omar, dates that make it impossible for them to have been students at a school in Nishapur.

Not everything in the legend of Omar Khayyam, Nizam el-Molk and Hassan ibn Sabbah is untrue. The relationship between Omar and Nizam really existed, and the mathematician and astronomer received an offer from the grand vizier to work as an astronomer and astrologer at the court of Sultan Malik Shah in Isfahan. There, Omar Khayyam worked as an astronomer and astrologer for eighteen years, perhaps the most peaceful years of his life.

What can be historically salvaged of the relationship between Khayyam, Nizam and Hassan was used by the Lebanese writer Amin Maalouf, with the natural help of some literary licence, to put together an excellent novel entitled Samarkand. It recounts the vicissitudes of an exquisitely illustrated manuscript containing the rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, from the time the mathematician and poet began to compose it in Samarkand around 1070 until the manuscript ended up sinking with the Titanic on the night of 14-15 April 1912.

References:

Antonio J. Durán, El ojo de Shiva, el sueño de Mahoma, Simbad… y los números, Destino, Barcelona, 2012.

Leave a Reply