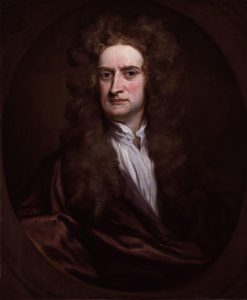

It is not uncommon to find attributed to Isaac Newton the famous phrase: “If I have seen further than others, it is because I have stood on the shoulders of giants”, in gratitude and recognition of what he learned from others. The phrase appears in a letter to Robert Hooke dated 1676.

The phrase is not original to Newton, and can be traced back in time to John of Salisbury (12th century), who in his Metalogicon (1159) quoting Bernard of Chartres wrote: “We are like dwarfs sitting on the shoulders of giants to see more things than they do and to see further, not because our vision is keener or our stature greater, but because we can rise higher because of their giants’ stature”.

The sentence, as Newton wrote it, is usually interpreted as a token of Newton’s gratitude to Hooke, on whose shoulders Newton had figuratively climbed to see further.

But the line also admits another, more twisted interpretation by Frank E. Manuel (1910-2003), who in the 1960s and 1970s carried out important studies on various facets of Newton’s personality. Manuel’s interpretation, based on the fact that Robert Hooke was short and somewhat hunchbacked, is as follows: “Newton replied on 5 February 1676 with a well-worn image frequently quoted in the literary quarrel between ancients and moderns over the idea of progress, an image that goes back at least as far as John of Salisbury and has often been quoted, on Newton’s behalf, out of context as evidence of his generous appreciation of the work of his predecessors: ‘If I have come to see further it is because I stood on the shoulders of giants’.” Placed where it belongs, in the psychological atmosphere of his 1676 correspondence, the tribute has a rather more complicated, even ambiguous, meaning; it is a double-edged sword. The image of a dwarf – not explicitly mentioned – standing on the shoulders of a giant sounds like an abrupt departure, until one realises that there is, on Newton’s part, something malicious in the application to his relationship with Hooke of this vulgarised simile. At first sight it seems as if Newton were calling Hooke a giant and suggesting that he is merely a dwarf by comparison; but the hyperbole was, after all, directed at a man of short stature and hunchbacked, and there is a tone of mockery here, conscious or unconscious, as when a fat man is called skinny and his obesity is thus emphasised”.

Robert Hooke is perhaps the greatest of 17th century English scientists – with the exception, of course, of Isaac Newton. Hooke lived his last years bitter and resentful, being aware of that exception, and that Newton would transcend the boundaries of science to become a famous figure in history: he seemed to guess that, as time went on, few outside the narrow world of science would know who Robert Hooke was, while Isaac Newton’s name would become famous even among the unlettered.

When Hooke died he was barely skin and bones, consumed by diabetes and by his hatred of Newton. A reading between the lines of his diaries shows a man defeated by the humiliation of knowing that posterity would remember him more for having been one of Newton’s many enemies than for his own merits. And yet there was no lack of merit in Hooke’s scientific career, with stellar contributions in physics, design and improvement of microscopes and telescopes, astronomy, biology or architecture – significantly, one of Hooke’s biographies is entitled: London’s Leonardo.

Evil tongues still attribute to Newton one last mischief carried out as President of the Royal Society on Hooke’s image. Despite Hooke’s scientific fame and the fact that he had himself been portrayed on at least a couple of times, no image of him has come down to us. Only several verbal descriptions have survived; two of them, from friends who frequented him, are quite consistent: both depict him as short, somewhat “crooked”, with a thin build and a large head. From time to time, news of the discovery of one of Hooke’s lost portraits circulates, only to be later denied. In 1939, for example, it was thought that one of his portraits had been found, but it soon turned out to be a mistake because it did not fit his description. In 2003, coinciding with the 300th anniversary of his death, the historian Lisa Jardine claimed to have discovered one of Hooke’s portraits; this time the image more closely matched the descriptions – in fact, Jardine used it as the cover for the biography of Hooke that she published, along with three other authors, in 2003. But it later turned out that the painting actually depicted the Flemish scientist Joan Baptista Van Helmont (1579-1644). As I say, some evil tongues attribute to Newton the responsibility for the loss of the portraits of Robert Hooke. During Newton’s time as president, the Royal Society moved house. Until then it used to meet on loan from Gresham College, but in the early years of the 18th century the College informed Newton that it could no longer rent the space it had at its disposal. In 1710 the Society bought premises and moved to Crane Court Street. It is possible that Robert Hooke’s paintings were lost in the move from one location to another.

References

F.E. Manuel, A portrait of Isaac Newton, Cambridge (Mass.), Harvard University Press, 1968.

A.J. Durán, Newton, La ley de la gravedad, RBA, Barcelona, 2012.

Leave a Reply