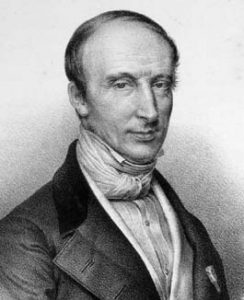

Looking at the situation in Catalonia yesterday, 1st October, it came to me a certain incident when the great French mathematician Augustin-Louis Cauchy went to cast his vote. As additional information to what follows, it is worth noting that Cauchy was a staunch supporter of the French Bourbon kings, a somewhat fanatical Catholic, and that he repudiated and hated, with intense and undying resentment, the French Revolution and what it meant for his country and for the world.

In 1830 the situation in France was very complicated. King Charles X was ready to return France to absolute monarchy. Discontent was growing in the streets, and two parties began to gather around a possible fall of the king: on the one hand the republicans, on the other those who advocated a continuation of the monarchy but with a more constitutional character and a change of king and dynasty. Charles X looked for an appropriate moment, dissolved the Chamber of Deputies and called elections for July. The king wanted the ultra-conservative camp to win the elections in order to curb the opposition that the liberals and constitutionalists had been making to him from the Chamber of Deputies. The elections were therefore important in an increasingly tense and difficult situation for the bourbon.

At that time the right to vote was not universal, but Cauchy was one of the privileged ones who could vote, and he went to vote… although aware of the delicacy of the situation, he did more than vote: “Mr Cauchy,” recounted a newspaper of the time on the day of the elections, “a member of the Académie des Sciences, is an elector and votes in the second section of the seventh college, which is located in the Sorbonne. This morning, when Mr Cauchy was called to cast his ballot, he found two lists on the table. Mr Cauchy expressed his indignation at seeing a list of liberal candidates next to that of the royalist electors. He then grabbed the list and crumpled it in his hands. First President Sèguier, who was standing next to Mr. Cauchy, reprimanded him and reminded him that just as he was free to vote for whomever he thought best, he should allow the other electors to write down the names of the candidates of their choice correctly. But Mr. Cauchy, paying no attention to Mr. Sèguier’s remarks, continued to shout and gesticulate vehemently while crumpling the list more and more. Mr. Cropelet, president of the second section, had to call Mr. Cauchy to order, to order him to return the list to its place and to ask him to leave once he had voted”.

King Charles X’s strategy, even with Cauchy’s help, met with little success, and the opposition won 274 seats to the 143 obtained by his supporters. Charles X opted for a self-coup, and on 25 July issued four decrees: restricting the freedom of the press, dissolving the newly elected Chamber of Deputies, further restricting the right to vote, and calling new elections. Two days later, Paris revolted, and for three days – 27, 28 and 29 July, which have come to be known in French history as the “three glorious days” – its streets were filled with barricades, mainly manned by workers, students and petit bourgeois, which brought down the last Bourbon king of France.

The Republicans then chose the Marquis de Lafayette as their leader, while the supporters of a constitutional monarchy tried to convince Louis-Philippe d’Orléans to accept the throne. Lafayette, a French hero during the American War of Independence, a promoter of religious freedom, the abolition of slavery and the declaration of the rights of man and citizen, had shown too much loyalty to kings. So perhaps there was nothing strange in the fact that, on 31 July, Lafayette stood on the balcony of the Paris City Hall, holding the hand of Louis-Philippe d’Orléans, and said: “Here is the best of republics”.

Charles X went into exile. And the hot-tempered Cauchy also went into exile. For love of the last Bourbon king of France? So say many of his biographers– but not all. A particularly well-informed one suggested another explanation: Cauchy set off on his journey alone. He had married Aloïse de Bure, daughter of a wealthy bookseller, in 1818. It was Cauchy’s father who had chosen a bride for his son, which points more to a marriage of convenience than of amorous passion. Augustin and Aloïse had two daughters, Marie Françoise Alicia, born in 1819, and Marie Mathilde, born in 1823. Neither the mother nor the daughters – the latter were then 11 and 7 years old respectively – accompanied Cauchy when he went into exile; in fact, it took the family four years to get back together: “What forces us to wonder”, wrote B. Belhoste in his biography of Cauchy “whether Cauchy did not decide to escape from family and marital responsibilities rather than from the revolutionary turmoil…”.

References

B. Belhoste, Augustin-Louis Cauchy, a biography, Springer-Verlar, Berlín, 1991.

A.J. Durán, Cauchy, hijo rebelde de la revolución, Nivola, Madrid, 20o9.

Leave a Reply