I think the first time I came across the word “guarismo” was when I was reading Azorín. It must have been when adolescence made pimples sprout on my face as easily as springtime makes orange blossom sprout on orange trees. As if that wasn’t tragedy enough, the teacher on duty came up with the idea that we children had to read Azorín’s Las confesiones de un pequeño filósofo; and I say wrong, because we not only had to read them, but also comment on them and look up in the dictionary all the words we didn’t understand. It is clear that the little philosopher Azorín had found the logarithm tables as terrible as I found his confessions, and he left proof of this in his book: “And I hastily opened a terrible book entitled Tablas de logaritmos vulgares (Vulgar logarithm tables). Why are these poor logarithms vulgar? What are the select ones, and why don’t I have them to look at? I immediately looked at this book and began to read it fervently; but I had to close it after a moment, because these long columns of numbers (guarismos in the original) frightened me to death…”. From that paragraph, I had to look up several words in the dictionary. One was “guarismo”, to which the dictionary (in its latest editions) attributes three meanings: “Pertaining or relating to numbers”, and also “Each of the Arabic signs or figures expressing a quantity”, and even “Expression of a quantity composed of two or more figures”. What the dictionary does not say is that “guarismo” is etymologically derived from al-Khwarizmi, although this would surely have been of little comfort to the little philosopher.

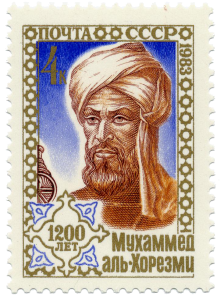

History has been ambivalent about al-Khwarizmi – which also admits the variations al-Kwowarizmi, al-Khorezmi… On the one hand, it has been sparing with regard to the information preserved about his life. Little else is known about him: he was a Muslim, born in Khwarizm, the semi-desert region south of the Aral Sea, a prominent member of the House of Wisdom in Baghdad, and that he was born around 780 and lived for about seventy years; we know that during those years he was an astronomer and mathematician, and perhaps also a translator – he may have been fluent in several languages: Arabic, of course, in which he composed his works, but also the Persian dialect spoken in Khwarizm and also Persian, and he must also have known something of Sanskrit and perhaps Greek and Syriac. But, on the other hand, history has been generous to al-Khwarizmi, for from his name derive, directly or indirectly, prestigious names in the mathematical, scientific and technological fields, such as algorithm, “guarismo” and algebra.

The curious thing is that, over the last 150 years, the academics of the language have put the term “guarismo” through a veritable ordeal. In the editions prior to 1869, the dictionary gave no etymology at all; it then went on to mention a mysterious Arabic word: “huarezmi”. The 1956 edition covers itself with glory because, although it mentions al-Khwarizmi in the etymology of “guarismo”, it

attributes to the Muslim scholar nothing more and nothing less than the invention of logarithms. The blunder is maintained in the 1970 and 1984 editions. Like the Guadiana, the etymology of “guarismo” disappears in the 1989 edition, reappears in the 1992 edition, with a mention of al-Khwarizmi but without attributing logarithms to him, and disappears again in the 2001 edition.

Another word in that paragraph that I had to look up was “logarithm”, for I had not yet been taught at school what logarithms were, although I had already heard of them as the most complicated and incomprehensible thing in the world, so much so that, as has already been said, language academics attributed their invention for some decades to al-Khwarizmi, when they were the independent invention of a Scottish nobleman, John Napier (1550-1617). (see Logarithms and the drunken moose), and a Swiss commoner, Joost Bürgi (1552-1632). Fortunately for my later professional career, that paragraph by Azorín not only did not predispose me against logarithms, but considerably increased my fascination with them. The dictionary did not clarify for me what “vulgar logarithms” meant, either, which so much angered little Azorín; some years later I learned that it was the name given to logarithms with base 10, also called decimals, to distinguish them from Napierian logarithms, which have the number \(e\) as their base. With academics like Azorín, it is not strange that the dictionary entry for the word “beauty” reads: “This property exists in nature and in literary and artistic works”, banning scientific works, in general, and mathematics, in particular, from the paradise of beautiful works. In short, that’s what academics are all about.

References

Antonio J. Durán, El ojo de Shiva, el sueño de Mahoma, Simbad… y los números, Destino, Barcelona, 2012.

Leave a Reply