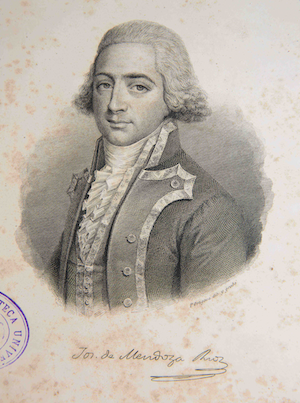

A few years ago the IMUS directors asked me to name the mathematical research colloquium shared by the IMUS and the IEMath-GR after an Andalusian mathematician, and I suggested José de Mendoza y Ríos (1761-1816) from Seville… and there is no shortage of reasons to have named the colloquium of the mathematics institutes of Seville and Granada after him.

Mendoza Ríos made important contributions to the astronomical resolution of the problem of longitude, which earned him one of the prizes awarded by the London Longitude Bureau. The problem of determining longitude at sea was one of the main, if not the main, problem that had confronted nautical science since the time of the discovery of America. Almost every country with transatlantic interests had offered prizes for its resolution, and numerous scientists – one of them Galileo – had taken an interest in it. Since the watchmaker John Harrison had made clocks in the mid-18th century that were sufficiently accurate and reliable to carry the time of a particular place on a ship, a technical solution to the problem was already available. However, at the beginning of the 19th century this solution was far from definitive: the clocks were extremely expensive, difficult to obtain and, in any case, it was convenient to determine the longitude from time to time by other means in order to be sure that the clock would not fail.

Mendoza Ríos made important contributions to the astronomical resolution of the problem of longitude, which earned him one of the prizes awarded by the London Longitude Bureau. The problem of determining longitude at sea was one of the main, if not the main, problem that had confronted nautical science since the time of the discovery of America. Almost every country with transatlantic interests had offered prizes for its resolution, and numerous scientists – one of them Galileo – had taken an interest in it. Since the watchmaker John Harrison had made clocks in the mid-18th century that were sufficiently accurate and reliable to carry the time of a particular place on a ship, a technical solution to the problem was already available. However, at the beginning of the 19th century this solution was far from definitive: the clocks were extremely expensive, difficult to obtain and, in any case, it was convenient to determine the longitude from time to time by other means in order to be sure that the clock would not fail.

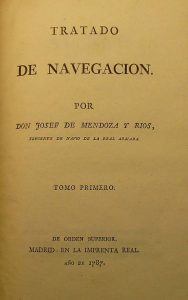

Mendoza Ríos devised an astronomical process for calculating longitude at sea by measuring distances between the Earth, the Moon and certain auxiliary stars. In an article published in the Philosophical Transactions of London in 1797, Mendoza Ríos described up to forty known procedures for clearing the distance after a series of measurements had been made, and explained his own based on the use, first, of an instrument: a reflection circle improved by Mendoza Ríos which made the measurements easier and more precise, and, second, of tables, which facilitated the subsequent calculation processes.  In today’s language, the methods for clearing the distance were algorithmic processes of repeated calculation with a region of convergence and another of chaotic behaviour: a small difference in the previous observations -that is, in the initial conditions of the iterative process- could generate large errors at the end of the calculations. Mendoza Ríos’s contributions consisted of a greater specification of the convergence region – which later took the form of a series of tips on how to carry out the measurements to avoid the chaotic region of the algorithm – and the simplification of the numerical algorithm through his tables. Mendoza Ríos published several volumes of tables; the best were those of 1804, of which a Spanish version was made in 1850 by José Sánchez Cerquero, then director of the San Fernando Observatory, leader of the group of mathematicians at the Observatory and responsible for the publication from 1848 in Cádiz of the Periódico mensual de Ciencias Matemáticas y Físicas, the first journal of mathematics and physics published in Spain. Of Mendoza Ríos’ method, Jean Baptiste Delambre – responsible for the measurement of the meridian arc that gave rise to the definition of our current unit of measurement: the metre – said: “of the various methods for calculating the distances from the Moon to the Sun and the stars, I gave absolute preference over my own and all others to those of Mendoza. This method has been further simplified with the publication of his Tables. This work is the most complete, the best conceived and the most convenient of all those that have appeared on nautical astronomy”.

In today’s language, the methods for clearing the distance were algorithmic processes of repeated calculation with a region of convergence and another of chaotic behaviour: a small difference in the previous observations -that is, in the initial conditions of the iterative process- could generate large errors at the end of the calculations. Mendoza Ríos’s contributions consisted of a greater specification of the convergence region – which later took the form of a series of tips on how to carry out the measurements to avoid the chaotic region of the algorithm – and the simplification of the numerical algorithm through his tables. Mendoza Ríos published several volumes of tables; the best were those of 1804, of which a Spanish version was made in 1850 by José Sánchez Cerquero, then director of the San Fernando Observatory, leader of the group of mathematicians at the Observatory and responsible for the publication from 1848 in Cádiz of the Periódico mensual de Ciencias Matemáticas y Físicas, the first journal of mathematics and physics published in Spain. Of Mendoza Ríos’ method, Jean Baptiste Delambre – responsible for the measurement of the meridian arc that gave rise to the definition of our current unit of measurement: the metre – said: “of the various methods for calculating the distances from the Moon to the Sun and the stars, I gave absolute preference over my own and all others to those of Mendoza. This method has been further simplified with the publication of his Tables. This work is the most complete, the best conceived and the most convenient of all those that have appeared on nautical astronomy”.

Born in Seville on 29 January 1761 – his birth certificate can still be seen in the parish church of San Martín – Mendoza proposed, at the end of the 1780s-90s, the creation of a naval research institute in Cádiz, which he named the Maritime Library. The institution would be aimed at the scientific modernisation of the navy, including in particular the improvement of mathematical training: the idea was to create a documentary centre of books and journals of the first order as a preliminary step to the creation of an institute that would enable the direct exchange of scientists with the centres of excellence in Europe. Mendoza Ríos’ project, with the support of the Count of Floridablanca, was initially accepted and the first stage was reasonably well developed – but not the rest – with an initial expedition in search of books and scientific instruments. Although going around Europe buying books doesn’t sound very adventurous, Mendoza Ríos’s life trajectory is a mixture of science and adventure -more of the latter than the former. Judge for yourself from the following sketch: Mendoza led the first expedition to buy books, whose initial destination was Paris at the beginning of the French Revolution, so during the three years he was there he travelled frequently to London and Holland, avoiding the most conflictive periods. During those years he sent crates and crates full of books and instruments to Cadiz: they form the basis of the most valuable collections that the San Fernando Observatory treasures today.

In 1792, fleeing the complicated French situation, he moved permanently to London, where he continued his work of acquiring bibliographical and technical collections. In London he soon found the protection of Joseph Banks, the then president of the Royal Society of London, a society Mendoza Ríos joined the following year. From London he sent a series of confidential reports on industrial organisation and planning, and also on the organisation of the English navy. Mendoza Ríos was always suspected, more or less well-founded, of espionage. On some occasions in favour of Spain because of the reports he sent from London; but he was also accused, more or less openly, of informing the English during the war waged against them at the beginning of the 19th century – with such decisive episodes for the Spanish navy as the defeat at the Battle of Trafalgar.

Another of Mendoza Ríos’s important actions was to commission William Herschel – the discoverer of the planet Uranus – and follow up on the construction of a large telescope for the Madrid Observatory; in fact, during his time in Paris he had worked on the coordinated construction between France and Spain of one with a platinum mirror – in the project, which did not come to fruition, the chemist Lavoisier also collaborated. The operation with Herschel was completed in 1796; the telescope built was, at that time, the second largest in the world and put Spain in a privileged position in the field of astronomical observation: if instead of locating it in Madrid they had taken it to Cadiz, where at that time there was a more modern scientific structure, it would have been possible to obtain different results – apart, of course, from the greater possibilities it would have had of surviving the French invasion of 1808.

That same year, 1796, he sent another shipment of books and documents to Cadiz: the task was extremely difficult as war had been declared with Spain. Mendoza Ríos asked to retire from the Spanish Navy as he had already decided to settle in London. This was not granted and, moreover, he was eventually expelled from the Navy in 1800 – we have already mentioned above the suspicions of making reports for England during that period of war. Mendoza Ríos never resigned himself and sought to have his status recognised; he even asked Godoy in 1806 to grant him the honourable retirement he had requested in 1796. Mendoza Ríos settled permanently in England, where he married and had two daughters. He committed suicide on 4 March 1816 at his home in Brighton, leaving a considerable fortune.

The books sent by Mendoza Ríos were definitively incorporated into the Astronomical Observatory in 1826, as a consequence of the closure of the Academy of Marine Guards in Cádiz, from which it had already separated at the beginning of the 19th century; since 1798 the Observatory already had its current building on the Isla de León, and a total of 5,423 volumes from Mendoza Ríos’ commission ended up there.

References

A. J. Durán, La ciencia en Andalucía, Cuadernos del Museo Memoria de Andalucía, 2008

José de Mendoza fue uno de las mentes matematicas más importantes de ese siglo, gracias por hacer una referencia a esta importante figura de la epoca.