We are used to scientists being important and even popular figures. What successful scientist does not try to publish a popular science book? Who does not seek to add to scientific success the bonus of popularity? Who does not want to be like the physicist Hawking, or the biologist S. J. Gould? And popularity can be associated with political influence, an invitation to a reception or a party, and so many other pleasant things.

We are so used to this, and so much importance is given today to diffusion, dissemination, transmission of knowledge, popularisation… (the list of key words is long!) that we may forget that in the past things were otherwise. So let the historian come and remind us of our condition as mortals, how contingent is the whole way of life that surrounds us.

There was a time when scientists were not media personalities, when a phenomenon like Einstein’s would have been beyond imagination. This was the case even in times when many wrote books that were easy to understand, because there were not yet enough experts to write in the “esoteric” way of the journal articles we are used to. Think of great physicists and mathematicians before 1900: Newton?, Weierstrass?, Gauss?, Euler?, Maxwell? – writing popular works? Absolutely not. Of course, the elusive and highly demanding (Newton, Gauss, Weierstrass) were not the people for that, far from it. From Euler we have his Letters to a German princess, but this is the literature of courtly life. And from the great Maxwell, we have lectures for a wide audience, and some generalist articles for Nature or the Encyclopaedia Britannica. That is already a big change, which tells us something about the 19th century, but nothing to do with the case at hand.

As early as 1916, Einstein published a book on relativity for people with no more than a high school education: a great book, which many of us have read in our youth. And the truth is that he was good at writing works of rigorous popularisation, which transmit without excessive complexity, and which have nothing to do with the highly imaginative or speculative ideas that we find in other books by recent physicists. I recommend The Evolution of Physics, a magnificent work done together with Infeld (if I remember correctly, there is not a single formula in this book, but there are many diagrams). On this subject, we should talk about the precedent set by Poincaré with his books, being a scientific character quite different from Einstein, but that is for another day…

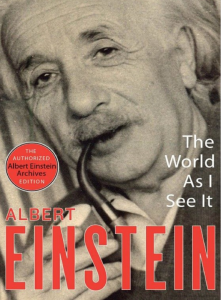

The fact is that the matter went much further. In 1949, The World as I See It was published, a book made up of articles, interviews, letters, speeches, in which the opinions of the great scientist on all kinds of subjects are touched upon: humanity and its future, the problem of peace, the mission of science, ethics, religion, society and politics.

Shortly afterwards, Ideas and Opinions appeared, which –I am just discovering now– has been selected by the Modern Library as one of the 100 best non-fiction books of all time. Here, in addition to the material in The World as I See It, there are also more substantial articles on physics, geometry, relativity, and so on.

So the figure of Einstein appears to us, once again, as something very singular. What a genius he was, we will say, inimitable! And in saying so we are forgetting that his case is typical of the times in which he lived. The Einstein media phenomenon tells us a lot about what Albert was like, but perhaps even more about what the 1920s, 1930s and 1940s were like. For it was in those decades that the world of the mass media consolidated, the heyday of magazines, newspapers, etc., which were soon joined by the world of radio. The same processes that generated the Hollywood superstars gave rise to the most famous scientist of all times.

And clever Albert, faced with this situation, found himself at ease and unleashed a feature of his personality. All this began early, around 1920, when the acceptance of General Relativity gave him a definite boost, and his face began to appear on front pages. He was able to astonish the world with his heterodox ideas (e.g. on religion), with his philosophical outlook on life, he could even make people laugh with his outbursts, and perhaps all this helped him to continue to be seen as the peerless sage, to be admired. It would also help him to forget (why not) hard experiences such as having to support the nuclear arms race, while being a pacifist; the terrible, tragic experiences of the 1940s in Germany, in the USSR… and so on and so forth, including his own personal shortcomings.

After the “Einstein case”, nothing would be the same, and the ground would be prepared for the arrival of the Asimovs, the Sagans, the Hawkings, the Watsons, and a long etcetera. Of course, sometimes, in the face of extravagant or even rather mediocre ideas that one reads out there, one misses good old Albert Einstein. What a brilliant guy.

Some references and recommendations

A. Einstein. Relativity: The special and the general theory. 1920, Henry Holt, New York.

—- Ideas and opinions. 1954, Crown Publishers.

—- The evolution of physics. 1938, Edited by C.P. Snow, Cambridge University Press.

L. Euler. Cartas a una princesa alemana. Universidad de Zaragoza, Prensas Universitarias, 1990. (See also Reflexiones sobre el espacio, la fuerza y la materia, Alianza Ed., 1985.)

J. C. Maxwell. Escritos científicos, edited by Sánchez Ron. Madrid, CSIC, 1998.

H. Poincaré. Ciencia e hipótesis. Madrid, Espasa Calpe, 2002. (And also El valor de la ciencia; Ciencia y método; Últimos pensamientos.)

Leave a Reply