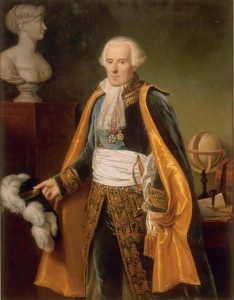

It has not been uncommon throughout history for scientists to attribute the harmony of the cosmos to God. Kepler, Newton or Euler did so. Lately, agnostics and atheists have become more abundant – it is about time – to the point that 90% of the scientists in the US National Academy of Sciences admit to being at least agnostic – in a country where 90% of the population say they believe in some god. One of the first scientists to expel God from the celestial realms was Pierre-Simon Laplace (1749-1827).

Laplace lived through the entire turbulent French revolutionary period, as well as the rise and fall of Napoleon, and the subsequent Bourbon restoration, and knew, like few others, how to surf such a historical, political and social storm while remaining, so to speak, always on the crest of the wave of political-scientific influence.

A member of the Académie des Sciences from an early age, he was also a mathematics examiner at several military academies, including the Artillery Academy in Paris, where Napoleon Bonaparte passed through his hands when he was a cadet in 1785. Laplace endured the revolutionary period well, becoming actively involved in all the scientific initiatives of the new regime, and reached his peak under Napoleon. In 1799, as soon as Napoleon came to power, he appointed Laplace Minister of the Interior, although he only stayed in office for six weeks. Why such a short time? Decades later, Napoleon wrote in his memoirs that Laplace was a clumsy politician who lost himself in subtleties whenever he had to act. In Napoleon’s own words: “He wanted to bring the spirit of infinitesimals into administration”. But perhaps it is more accurate to say that Napoleon used Laplace’s prestige to his advantage: he appointed him immediately after his coup d’état, possibly to entice the favour of the prestigious scientific sector where Laplace was so influential, and knowing that he would only keep him until he had consolidated his power, after which he dismissed him and put in his place someone he trusted more: his brother Lucien Bonaparte.

Nevertheless, Napoleon honoured Laplace by making him first a senator, then President of the Senate – both positions so well paid that they made him a rich man – and finally Count of the Empire. Laplace, in turn, included flattering dedications to Napoleon, “the peacemaker of Europe”, in both the third volume of his Celestial Mechanics (1802) and his Analytical Theory of Probabilities (1812) – discreetly removed in later editions printed during the Bourbon restoration. After the disastrous Russian campaign, Laplace began to move away from the emperor and towards those working for the Bourbon restoration. When the restoration took place, Laplace was appointed marquis.

Of the relationship between Napoleon and Laplace, an anecdote has been recorded in history about the former’s mischievousness in asking questions and the latter’s sharpness in answering them: when Laplace offered Napoleon a copy of one of his books on astronomy, the latter asked: “I am told that in this great book you have written on the system of the world there is no mention of God, its creator”, to which Laplace replied: “Sire, I have had no need of that hypothesis”. As with many of history’s greatest sentences, this one is possibly apocryphal; Laplace’s meeting with Napoleon in 1802 was witnessed directly by William Herschel – the discoverer of the planet Uranus – who recounted it in one of his journals, and although Laplace and Napoleon argued about who had created the universe – a chain of natural causes, which was also responsible for its preservation, according to Laplace; that plus divine intervention according to Napoleon and Herschel himself – Laplace does not seem to have used that brilliant phrase as an answer.

References

A.J. Durán, El universo sobre nosotros, Crítica, Barcelona, 2015

¿Ya era hora? Ah, vaya.

Excelentes datos históricos tanto de Napoleón cómo dé Laplace siendo este último un científico eminentemente agnóstico con el cual me identifico casi en su totalidad