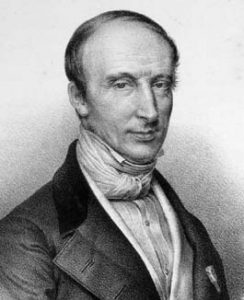

In the summer of 1833, the great French mathematician Augustin Cauchy was in his third year of exile. Cauchy, convinced of the divine right that bound the French Bourbons to the throne, had left France in 1830 after Charles X, the last Bourbon king of France, was deposed – see my post Voting with bad manners. Charles X and his entourage took up residence in Prague, in a palace provided by the Austrian Emperor Franz II, while Cauchy had found a home in Turin under the protection of King Charles Albert of Piedmont-Sardinia.

Cauchy then received a commission that must have tasted of glory: “Happy to be out of the political scene,” Cauchy wrote, “and totally devoted to the culture of science, I had just brought to light two new calculations that seemed to me to be of interest to geometricians, I was dreaming of publishing my works on number theory and completing those on the theory of light, when an order from the King of France came to take me out of this peaceful retirement to entrust me with the education of the heir of Saint Louis, Henry IV and Louis XIV”.

Cauchy did not quite know what a hornet’s nest he was getting into.

The pretender to the throne to be educated was the Duke of Bordeaux, Henri by name. The grandson of Charles X, he was then 13 years old and, after Charles X abdicated, had become the Bourbon pretender to the throne of France.

When Cauchy arrived in Prague, the situation was not the best.

First of all because the Duke’s mother, Marie-Caroline, Duchess de Berry, decided to return to France to try, on the spot, to prepare a revolt to restore her son to the throne. She was arrested and imprisoned, and the revolt eventually failed, giving way to a somewhat grotesque scandal when it was revealed in February 1833 that Marie-Caroline had remarried and was pregnant by her new husband.

Aside from the Duchess de Berry’s excesses, there were two opposing camps over the education of the Duke of Bordeaux, one old-fashioned and traditionalist, led by the Jesuits, and the other somewhat more liberal. The former had lost some support, as it was known that the Jesuits had a lousy reputation in France, and it was feared that being educated by the Jesuits would make the duke less likely to reign again.

When Cauchy joined the court in exile to assist in the education of the Duke of Bordeaux, he entered it like a bull in a china shop. Cauchy aligned himself with the Jesuits, and caused a conflict with his egregious pupil’s tutor, who was on the more liberal side, which led to the tutor’s resignation in early 1834.

However, Cauchy’s greatest problems came from the very pretender to the crown whom he had to educate. The Duke of Bordeaux turned out to be a badly educated and spoiled brat; that’s the thing about monarchies: if a stupid or foolish king emerges – which is not uncommon: see the catalogue of Spanish kings, queens, princes, princesses, infantas and infantes of the last three centuries – he cannot be removed by voting, that civilised way of doing politics, but by a revolution, where politics is also done, but in a somewhat more uncivil manner.

Cauchy ended up more than paying for his contribution to the duke’s bad education, because one of the disagreements Cauchy had with the former tutor was caused by the degree of tolerance our mathematician showed for the duke’s bad behaviour, excessively permissive according to the former tutor, and appropriate, according to Cauchy, taking into account the high birth of the student.

It is hard not to feel some sympathy for poor, stuffy Cauchy who had to put up with all sorts of humiliations and abuse from his beloved prince. He endured the royal pupil bombarding him in class with snowballs brought back from his walks, and, on another instance, the duke grabbing him by the throat and throwing him out of class in one of his frequent outbursts of rage; Cauchy’s reaction to such an offence was to apologise and ask the royal aggressor what he had done to displease him. At other times, Cauchy himself had to get down on his knees to pick up the objects that the spoilt youngster had been tempted to throw on the floor.

And the only thing that Cauchy succeeded in doing was that the Duke of Bordeaux ended up hating mathematics, and physics and chemistry, whose training he was also in charge of. “But what is so interesting about these numbers and drawings that Mr Cauchy always makes me study?”, complained the duke after suffering the poor attitude that Cauchy always seemed to have for teaching: “One of the things that encouraged the young man’s dislike of mathematics was that he never understood what it was that he was being taught,” the former tutor once recounted. “One day I personally attended one of the classes, during which the professor was demonstrating one of the simplest propositions of geometry. I noticed that the prince became more and more agitated, and more and more confused, and I had to admit to myself that, although I remembered that proposition very well, I could hardly follow what Professor Cauchy was explaining”.

In the autumn of 1838, the Duke of Bordeaux turned 18 and ended his training. Cauchy, urged on by his friends in Paris and especially by his mother, and no doubt fearing that he might be entrusted with the education of some other Bourbon, took advantage of the circumstance, put an end to his exile and returned to Paris. During the five years that Cauchy spent educating the Duke of Bordeaux, he hardly published anything and could do little more mathematical research than jot down the ideas that came to his mind to develop them later.

References

A.J. Durán, Cauchy, hijo rebelde de la revolución, Nivola, Madrid, 2009.

Leave a Reply