There is something spooky in the simplicity of the Newton’s apple anecdote, and in how useful it has been throughout history in popularising the figure of Newton as a genius. Something similar had happened before with Archimedes and the Eureka! anecdote.

Newton probably understood very well that the halo of genius that had surrounded Archimedes since time immemorial had to do with the excellence of his discoveries, but also with certain striking stories recorded by the chroniclers of antiquity. The most famous of these is the Eureka story – who, regardless of their cultural level, does not know it today? – but there are also many others with an undeniable propagandistic capacity. Newton managed to come up with a story that, in the end, was to have as much or even more power than the Archimedean Eureka! And I have written “managed to hit upon”, because it was Newton himself who, already in his seventies, used to tell the anecdote to anyone who came within reach – up to four independent versions have been preserved, all of them told by an elderly Newton. One of them was told to William Stukeley, Newton’s compatriot who was preparing a biography of Sir Isaac. Newton told it to him shortly before he died and, naturally, Stukeley included it in his Life of Newton (1752): “After lunch, the weather being warm, I went into the garden to take tea with Sir Isaac; under the shade of some apple trees, he and I were alone. Among other things, he told me that it was in that very situation that the notion of gravitation had occurred to him. It was suggested by the fall of an apple when he was sitting in contemplation. Why does the apple always descend perpendicularly to the ground, he asked himself, why doesn’t it go the other way or upwards? Surely the reason is that the earth attracts it. There must be a power of attraction in matter: and the sum of the earth’s power of attraction must be at the centre of the earth, and not somewhere else on the earth. That is why this apple falls perpendicularly or towards the centre of the Earth. There is a power, like that which we call gravity here, which extends to the whole universe”.

The way Newton told the story of the apple, it would seem that he saw the apple fall and the whole dynamic of planetary motion became clear in his mind. Newton’s inclination, especially in the last years of his life, to emphasise his visionary genius as opposed to the more prosaic, if more real, tireless worker, is also apparent in other descriptions of how he made his discoveries: “I kept the problem constantly before me, and waited until the first dawns slowly, slowly, slowly turned into full, clear light”.

Hardly anything is further from the truth than this simplistic view of the Newton who owes everything to genius inspiration. Anyone familiar with the whole process that led Newton to make one of his greatest scientific discoveries, the theory of gravitation, and to compose his magnum opus, the Principia, knows what I mean: the enormous difference between those supposed flashes of genius by which a discovery becomes apparent, single-handedly, in barely the time it takes for an apple to fall from the tree – the simplistic view of genius that is often associated with Newton – and the arduous, painstaking, time-consuming process of conceiving a germ of an idea, refining it, sorting out what is essential from what is bargain or even error, fitting it in with other ideas, until it is brought into being, labouriously, not without pain and often aided by what others have discovered or investigated before, what is properly a discovery – the real vision of what Newton did.

Hardly anything is further from the truth than this simplistic view of the Newton who owes everything to genius inspiration. Anyone familiar with the whole process that led Newton to make one of his greatest scientific discoveries, the theory of gravitation, and to compose his magnum opus, the Principia, knows what I mean: the enormous difference between those supposed flashes of genius by which a discovery becomes apparent, single-handedly, in barely the time it takes for an apple to fall from the tree – the simplistic view of genius that is often associated with Newton – and the arduous, painstaking, time-consuming process of conceiving a germ of an idea, refining it, sorting out what is essential from what is bargain or even error, fitting it in with other ideas, until it is brought into being, labouriously, not without pain and often aided by what others have discovered or investigated before, what is properly a discovery – the real vision of what Newton did.

Although it was not the rule, Newton himself occasionally acknowledged all that he owed to his enormous capacity for work; and so, in a letter dated 10 December 1692, he wrote that he owed the Principia only: “To industriousness and patient thought”.

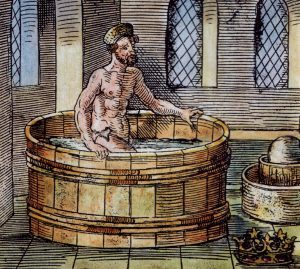

And the story of the apple is not the only story that links Newton’s anecdotes to those of Archimedes. “Archimedes, continually flattered and entertained by a domestic and familiar siren,” recounted Plutarch in the Life of Marcellus, “forgot his food and took no care of his person; and being forcibly driven to anoint and bathe himself, he formed geometrical figures in the very hearth, and after anointing himself drew lines with his finger, being truly beside himself, and as it were possessed by the muses, for the supreme pleasure he found in these occupations”. Newton made a puritanical version of this anecdote, which shows a ludic and playful Archimedes, smeared with oil by a personal attendant: “I know not what I may appear to the world,” he once recounted, “but I look upon myself only as if I had been a child playing on the seashore, and amusing myself by finding now and then a smoother pebble and a more beautiful shell than ordinary ones, while the great ocean of truth remained undiscovered before me”.

References

A.J. Durán, Crónicas matemáticas, Crítica, Barcelona, 2018.

Leave a Reply