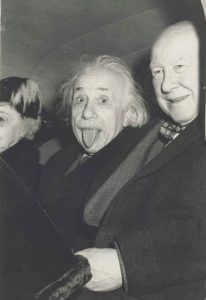

The intensity of Einstein’s marriage with the media was a singular sociological fact (see the posts Einstein superstar: the invention of the celebrity scientist, The exquisitely stupid questions of the reporters).

Einstein’s dizzying rise to media stardom came just over a century ago, in November 1919 (the 7th to be precise), when the Times of London reported on the meeting where the results of the study of the deflection of light by the Sun’s gravity in the eclipse of 1919 were made public (see Einstein, Newton and the eclipse a century ago).

But Einstein’s marriage with the media was undoubtedly also due to the fact that, for better or worse, the media had identified in him almost all the clichés of the scientist, a circumstance they exploited to the hilt. To the extent that journalists paid more attention than physicists themselves to Einstein’s unsuccessful attempts to create a unified field theory –with which he tried, unsuccessfully, to unify gravitation and electromagnetism– something that interested few physicists at the time, who were more interested in the advances of quantum theory and research into the atomic world.

This led to more than one Kafkaesque episode in Einstein’s life, as when in 1929 he published one of his many versions of unified field theory, yet another frustrating and failed attempt, incomprehensible to even the most educated physicists, and to which they paid little attention. Nevertheless, the world press followed the events of the weeks leading up to publication as if they were those of a great sporting event; and when the work finally saw the light of day, the Prussian Academy sold several thousand copies – when it was customary to put a few hundred into circulation – one of which was displayed page by page in the windows of a London department store as an advertisement, as if the arcane mathematical formulae and equations it contained had more drawing power than the then incipient and irresistible neon lights. An American university paid a fortune for the original manuscript. The article was telegraphed in full to New York – for which a coding system had to be devised to send the formulas – and published in full by the New York Herald Tribune. The New York Times sent reporters to several New York churches to echo what was to be said in several sermons about Einstein’s new theory – among other pearls: that it confirmed St. Paul’s synthesis and the oneness of the world, or that it was a decisive step towards universal freedom.

Similar media hype also occurred on other occasions when Einstein claimed to have completed his unified field theory; thus, in 1935, the New York Times published on its front page the following flowery report: “Climbing a hitherto unclimbed mathematical peak, Dr. Albert Einstein, mountaineer of the cosmic Alps, reports that he has sighted a new pattern in the structure of space and matter”; and in 1939 another no less exuberant one appeared on its front page: “Albert Einstein revealed today that, after twenty years of constant search for a law that would explain the mechanism of the cosmos in its entirety, ranging from the stars and galaxies in the vastness of infinite space to the mysteries that lie at the heart of the infinitesimal atom, he has finally come in sight of what he hopes will be the “promised land of knowledge”, which holds what may be the master key to the enigma of creation.”

And how to understand the history of the manuscript of his paper on special relativity? In 1943, he was asked to donate the manuscript to an auction to raise funds for the war effort. Einstein acknowledged that he had thrown away the manuscript shortly after his 1905 paper was published, but he was willing to rewrite the paper in his own handwriting; he did so, and the new manuscript was purchased by a Kansas City insurance company for six and a half million dollars. When Einstein heard of this, he could not help a corresponding dose of sarcasm: “Economists will have to revise their theories of value”.

Referencias:

- A.J. Durán, El universo sobre nosotros, Crítica, Barcelona, 2015.

Leave a Reply