The IMUS, with the participation of the Faculty of Mathematics, will hold a one-day event on Wednesday 19 February to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the passing of the Indian mathematician Srinivasa Ramanujan.

In the history of mathematics there is no shortage of unique characters; there have been those with an intense emotional life, as well as a scientific one, and others who have been torn apart by the historical, political and social circumstances in which they have lived, whether by luck or misfortune. Of all the leading mathematicians in history, Srinivasa Ramanujan, being in 2020 the hundredth anniversary of his death, has undoubtedly been the most inexplicable. One of his first biographers was able to condense in one sentence the impetus with which he spent his life: “Like a meteor, Ramanujan suddenly appeared in the mathematical firmament, crossed the short duration of his life quickly, burned out and disappeared just as quickly”.

Born in 1887 in a village south of Madras into a family of poor Brahmins, Ramanujan was unable to obtain even the equivalent of a bachelor’s degree, and not so much for economic reasons, but because he was never interested in any study other than mathematics. He was a “special” boy who fell under the spell of numbers and managed to raise a superb mathematical building from scratch. And he did it alone, without the help of anyone, sitting at the door of his house, writing on a blackboard and erasing with his elbow.

When his theorems and formulas began to transcend, the small scientific community of Madras was unable to determine whether he was facing a genius or a lunatic. Realizing that no one in his immediate environment could understand his formulas, Ramanujan decided to send them to Cambridge, then the centre of English mathematics. But neither the first letter he sent, nor the second, had any effect, because the English professors to whom they were addressed were too busy to try to understand what an unknown office worker in the port of Madras was sending them. The third letter fell into better hands, those of G. Harold Hardy; he was then 35 years old, a pacifist in times of war, a non-practicing homosexual –in the words of his closest collaborator– a stylist in mathematics, a gourmet in numbers.

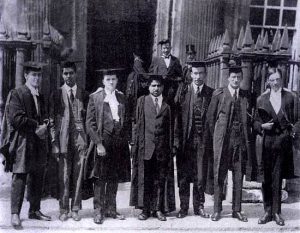

Hardy took Ramanujan’s letter seriously and, after thoroughly studying what the Indian clerk had sent him, he left no stone unturned until he managed to get Ramanujan to Cambridge. He arrived there in 1914, almost coinciding with the beginning of the First World War. Hardy could see that Ramanujan was an uncut diamond: he had a monstrously refined intuition for numbers and formulas, but he was unaware of basic concepts and tools that any aspiring mathematician must master in the early years of his career. But the miracle happened, the impossible happened, because Ramanujan, who had mathematically trained himself on the porch of his house in the deep south of India, was able to collaborate fruitfully and on an equal footing with Hardy, one of the most successful fruits of the prestigious English educational system.

Ramanujan spent almost five years in England –during which the First World War took place– although the last two years he was ill and interned in various health centres; the loneliness, the humid climate of the English countryside and the severity of an inflexible diet –Ramanujan was strictly vegetarian– aggravated by the shortage of quality food during the war, made him sick with an illness that none of the various doctors who attended him could diagnose properly.

Ramanujan returned to India in 1919, but only to die. He left his country lush and verdant and returned consumed by illness; he left as an unknown and returned as a celebrity: he was elected a member of the Royal Society of London, the youngest member in its century-old history and the second of Indian nationality – the first was elected in 1841 – and the first Indian to be made a fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge; the Times of Madras dedicated an article to him shortly after his arrival, where it could be read: “As someone in Cambridge has said, no one has been like him since Newton, which needless to say is the highest praise”. Ramanujan died in April 1920 at the age of 32.

In addition to his published works –mostly during his stay in England–, whether with Hardy or by himself, Ramanujan left a collection of notebooks full of formulas and theorems. Until very recently, the mathematical community has not come to understand the full meaning of many of Ramanujan’s formulas; and that meaning is of such transcendence and depth that it has ended up taking him to the Olympus of the greatest mathematicians in history.

Ramanujan was, without a doubt, a “special” person, a “brilliant” and “inexplicable” mathematician who, in the words of Hardy: “would have become the greatest mathematician of his time”; a guy, in short, “interesting”. He was, moreover, in an exaggerated way. And the more folds, the more nooks and crannies of his biography one knows, the more inconceivably exaggerated will be that “special”, “interesting”, “brilliant” and “inexplicable” nature that affected that descendant of the deepest India: because with Ramanujan what usually happens with these phenomena cannot be explained or understood.

References

Antonio J. Durán, El ojo de Shiva, el sueño de Mahoma, Simbad… y los números, Destino, Barcelona, 2012.

Sencillamente maravilloso, más aún cuando, en la actualidad existen teoremas son su debida comprensión

Qué hermosa, enigmática y mística esta historia. Quiero saber más de este hombre de las matemáticas.