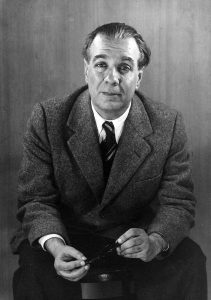

I said in my previous post Borges, Kafka and Munch (I), that both Borges and Kafka reflected infinity in some of their stories and novels, but while Kafka’s infinity would correspond to Aristotle’s infinite potential, Borges’ infinity would be more like Cantor’s actual infinity.

Let us focus on The Library of Babel (1941), which Borges included in the Fictions collection (1944). The story is written in the first person by one of the inhabitants of the Library – in capital letters. The Library is the only possible universe for those who inhabit it; the Library is composed of an indefinite number of hexagons, each with a ventilation shaft in the middle protected by a railing. There is a particularly intense paragraph; the one who writes can feel death close to him: “Dead, there will be no lack of pious hands that will throw me over the railing; my grave will be the unfathomable air; my body will sink for a long time and will be corrupted and dissolved in the wind generated by the fall that is infinite”.

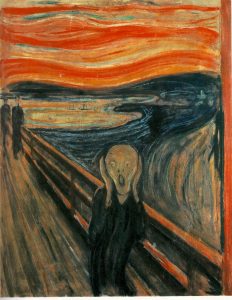

Whenever I read that passage from Borges, the painting The Scream (1893) by the Norwegian painter Edvard Munch comes to mind. The anxiety of that painting reflects well the vertigo of the fall described by Borges. After much thought I have come to understand why this paragraph from The Library of Babel evokes the painting.

Munch’s painting produces distress, uneasiness, perhaps because the cry is not heard: it is felt, but not heard. Not hearing the scream, which is nevertheless perceived, provokes anguish because it keeps us waiting, as it seems that we are going to start hearing it at any moment. When I read the paragraph of Borges’ story, I think of the body that falls and decomposes in the infinite fall, and I feel that the vertigo of the fall must make the one who falls cry, but what falls is a dead body and its scream must be mute: like the scream in Munch’s painting. I must confess that I found it rather disturbing to know that the object that inspired Munch’s face in The Scream was a half-decomposed Inca mummy that he saw at the Great Universal Exhibition in Paris in 1889.

I guess that the relationship between Borges’ paragraph and Munch’s painting is also influenced by Borges’ explicit mention of the infinity of the fall. Because the symbolic force of the painting, the dramatic use of perspective, the unreality and violence of the colours, suggest disproportionate aspects, close to the infinite, to the infinite anguish of the one who is screaming. In fact, Munch thus described the sensation that led him to paint that picture: “Alone, trembling with anxiety, I felt the cry, vast, infinite, of nature”. So the painting is also related to the word infinity. But that infinite is, and therefore is the infinite in action that Aristotle hated so much and that Cantor managed to tame with his research at the end of the 19th century.

By the way, the works of Edvard Munch caused an artistic controversy in Germany close to the mathematical controversy generated by Cantor’s works… And on dates not too apart. On 5 November 1892, Munch’s exhibition opened in Berlin. It was closed a week later, giving way to a harsh controversy: it was called The Munch Affair. During the debate there was much and bitter discussion about the limits of the artist’s freedom… This is undoubtedly very suggestive, because Cantor heard the same kind of music, which led him to say that “the essence of mathematics is freedom”. And with the passing of time both works, Cantor’s and Munch’s, have had enormous influence. Cantor’s ended up generating the theory of sets: the ambient space where all mathematics has been developed since the first decades of the 20th century. And Munch’s is not only perceptible in the German expressionist groups –Die Brücke, for example– but also in Picasso –the influence of The Scream in Guernica is noticeable.

And there is still one last disturbing similarity between Munch and Cantor: Munch also suffered nervous breakdowns, although perhaps not as severe or persistent as those that afflicted Cantor.

References

A.J. Durán, Pasiones, piojos, dioses… y matemáticas, Destino, Barcelona, 2009.

Leave a Reply