Almost three months ago, we launched the COVID-19 Emergency section in this blog to make Mathematics cast some light and perspective on the situation caused by the coronavirus epidemic. The first entry was published on 19 March and was entitled “Covid-19: early confinement helps save lives”, updated on 26 March.

Now that the outbreak has been brought under control, on the verge of abandoning the state of emergency and with more complete and reliable data at our disposal, we can see that the figures we gave in the 26 March update were reasonably accurate: we estimated between 18,000 and 25,000 deaths on 19 April in the event that the peak of the epidemic occurred on 31 March. We know today that it was around that date that the peak occurred and that 20,453 deaths were finally recorded on 19 April.

However, as we indicated at the time, the aim was not so much to estimate the number of deaths correctly as to quantify the influence that rapid and strong confinement measures could have on the evolution of the number of deaths caused by the epidemic. And the conclusion was clear: the total number of deaths is greatly influenced by the date at which confinement begins.

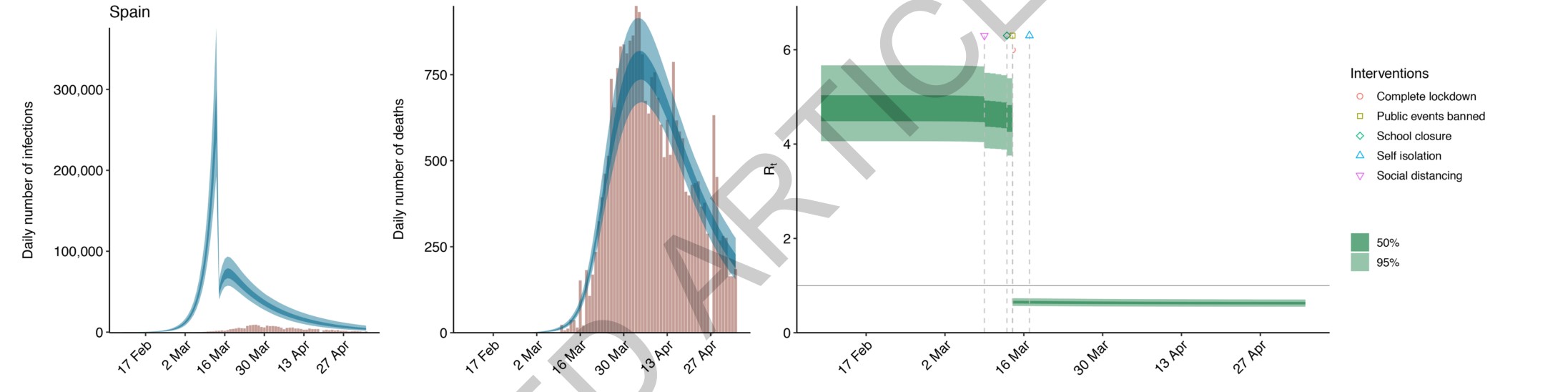

This conclusion has been confirmed by a study by the Imperial College published a few days ago, on 8 June, in the prestigious journal Nature. The study had been released at the end of March and contained estimates of the impact of the coronavirus in 11 European countries (we devoted here an entry to that study). The version featured in Nature has some updates on the initial study, the most striking of which is an estimate of the number of deaths that would have occurred in the different countries if governments had not taken any confinement measures. For Spain, this study gives some shocking figures: if the study’s basic hypotheses were true, there would have been (with a 95% probability) between 390,000 and 560,000 deaths.

Despite being so large, these figures are quite reasonable, as the following simple statistical calculation shows. Today we know that the epidemic grew in Spain with great strength (in an exponential rate) during the first weeks of March, to the point that, despite the severity of the confinement, the virus had infected some 2,300,000 Spaniards by early May, according to the JAN-COVID-19 seroprevalence study (also commented in this Blog).That number of infected people generated some 27,000 deaths (counting those up to 15 May). This gives the epidemic in Spain a lethality of 1.17%. With these figures of infected people, it is not unreasonable to think that if no confinement measures had been taken the virus would have ended up infecting more than two thirds of the population in a few weeks, before the epidemic was slowed down by the group immunity that would then have started to build up. This means that there would have been more than 30 million people infected in Spain. If we apply the lethality of 1.17% (lower than that which would certainly have occurred after the absolute collapse of the health system) it gives more than 350,000 deaths; a figure compatible with that given in the Imperial College study.

From all this, it can be concluded that the title of the first entry published in this Blog on the coronavirus epidemic: “Covid-19: early confinement helps save lives”, was quite accurate, even though now, with the outbreak under control and with much more knowledge, it could be refined: confinement has saved hundreds of thousands of lives.

Two more things to go:

Confinement worked because the vast majority of citizens in this country took it quite seriously. Naturally, not everyone behaved in a minimally responsible manner, as shown by the various parties and gatherings held by aristocrats, footballers and other such fauna –as was reported in the media. But the vast majority has proved, in very challenging circumstances, the responsibility of mature and committed people.

However, we should not forget how absent-minded we were at the end of February about the seriousness of the epidemic that was coming upon us. To fix ideas, let’s go back to March 1. Perhaps on that day we began to realise that the epidemic was going to cause us a few problems, although not enough to give up on attending a live football match or a concert, a demonstration in support of justifiable causes, or a meeting of our favourite political party. This spirit of the first of March –“I am worried but unwilling to give up something”– seems to be returning. We are worried, much more so than on the first of March, even though we are probably better prepared to detect a resurgence and control it, but perhaps not so much, so we are beginning to think that there is no reason to give up on attending a live football match or a concert, a demonstration, my favourite beach or the town’s festival. And we must be careful, because this virus only needs another dose of the spirit of the first of March to enter again in an exponential rate.

Leave a Reply