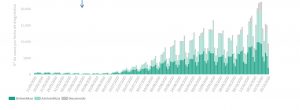

Using the methodology explained in two previous posts (this one and this one), one could deduce on 23 September that between 10,000 and 40,000 infected per week could have gone undetected during that month.

If we apply the same methodology to the data from the last days of October in Spain (with an average for the accumulated deaths in the previous seven days close to 700), it would give us an estimate for the accumulated number of actual infected in the week of 1-7 October of between 70,000 and 140,000 (bearing in mind the delay between death and infection); given that at the beginning of October some 50,000 cases per week were being detected, the conclusion is that it is very likely that between 20,000 and 90,000 infected per week were not detected during October. This suggests that the epidemic has entered an exponential phase that is comparable to what happened in early March.

Data from the end of September already recommended lockdown, which perhaps should not have been applied to the whole country as in March, but could have been more targeted, and applied in much smaller areas. But what did seem crystal clear was that confinement was necessary. As is well known, these containment measures were not taken (what they call “perimeter containment” is something very different from what was done in March, and does not correct the situation of the populations inside the perimeter when the number of infected there has skyrocketed).

The situation at the end of September also suggested a return to a state of alarm in order to guarantee the efficient implementation of local containment measures. And as is also well known, the state of alarm has only been in place for a few days (and it is not clear that with the form approved at the Parliament, containment measures like those of March and April can be implemented, even if they are local and not global).

From the above estimates (between 20,000 and 90,000 actual undetected infected per week in October) it can be inferred that there are possibly hundreds of thousands of infected undetected by the end of October, driving the epidemic forward. There is little doubt that in the last three or four weeks the virus has surprised us again and has entered an exponential phase (here in Spain and also in many European countries: France, England, Belgium, etc.).

This means that early detection by primary health care and tracing –which has actually never worked well in Spain– are of little use and will sooner rather than later lead us to house lockdowns similar to the one we had in March. The curfews and perimeter confinements decided in the last few days would probably have been ineffective a month ago, so they will not substantially change the situation now. If we add to all this the hospital overcrowding and the increase in deaths (I recall that the deaths reflect the epidemic situation three weeks or so ago), it seems that the conclusion is clear: in a large part of the country we have to go to house confinement of the kind we had last spring.

Hospital overcrowding was explained quite well by the president of the Andalusian government on Wednesday 28 October. In a message in which he was to announce measures against the pandemic under the state of alarm, the president recalled that the situation in Andalusia’s hospitals today was like that of the first days of April and clarified that, while at that time we had already been confined for three weeks and the curve was beginning to bend, now the curve continues to grow. With this explanation, the most reasonable conclusion would have been to communicate a confinement in Andalusia (or a large part of it) like the one in spring. But alas, the decision in Andalusia has been a perimeter containment of questionable effectiveness.

We must recall, once again, that delaying home confinement when the virus is advancing exponentially ends up having a cost in deaths that increases exponentially with the delay (it is quite possible that, if we had been confined on 7 March instead of 15 March, deaths in Spain during the first wave would have been reduced by between half and two thirds: between 13,000 and 18,000 fewer deaths). The delay also means longer lockdown periods to contain the virus. The conclusion from this is that delaying the decision to contain is the most damaging to the economy. The situation in Granada and its metropolitan area serves as an example. At the beginning of October the cumulative incidence of cases detected in the last 14 days (close to 500 per 100,000 inhabitants) suggested that some form of containment was necessary, but to save the economic activity associated with the long weekend of 12 October nothing was decided until it was over. Then a perimetral containment was decided which has proved incapable of even tempering the growth of the epidemic (Granada now exceeds 1,000 cases detected per 100,000 inhabitants in the last two weeks). The current epidemiological situation in Granada is abysmal, and it is certain to lose the economic activity associated not only with the All Saints and Constitution long weekends, but also with Christmas.

Tarde o temprano saldremos de esta. Lo importante es tomar las medidas de seguridad necesarias y comportarnos con cabeza.