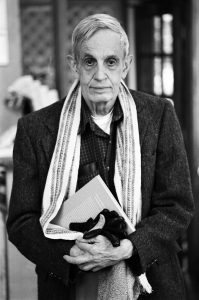

The 1994 Nobel Prize in Economics went to John F. Nash, Reinhard Selten and John Harsanyi for their analyses of equilibrium in non-cooperative game theory. The first of them, John Nash, was not an economist but a mathematician (and, to a lesser extent, something similar can be said of the second).

Nash (1928-2015) has some very deep theorems. For example, his 1951 result concerning the immersion of differential varieties. Nine decades earlier, Bernhard Riemann had described the \(n\)-dimensional varieties as geometrical objects of \(n\) dimension from which we know that each point is given by \(n\) coordinates \(x_1,\cdots ,x_n\), and the way to measure distances between their points, defined by the arc length element

$$ ds^2=\sum_{i,j=1}^n g_{i,j}dx_idx_j $$

where \(g_{i,j}\) are functions of the coordinates. The Euclidean space corresponds to the case \(n=3\) and \(g_{i,j}=1\) and the differential geometry that Gauss had developed three decades earlier would be the particular case when \(n=3\) (although Riemann, unlike Gauss, distinguished between the variety and the metrics \(ds^2\) that could be established on it; the variety would be for Riemann a topological concept that would acquire properly geometric characteristics when provided with a metric). Half a century later Einstein would use the Riemannian varieties to formulate his theory of general relativity (which, in some way, transformed the physics of the universe into differential geometry).

So, Nash’s surprising theorem assures that every Riemannian variety is isometric to a sub-variety of a Euclidean space, at the cost of increasing the dimension of Euclidean space over the original variety.

A few years later, Nash began to show strange behaviour, persecution manias and other behavioural disorders. He was diagnosed with schizophrenia, fought the disease for a quarter of a century, and eventually recovered by the end of the 1980s.

Nash became a worldwide celebrity as a result of the biographical film A Beautiful Mind (2001), directed by Ron Howard, in which Russell Crowe played the role of John Nash. The film was based on Nash’s excellent biography written by Sylvia Nasar and published in 1998; in the first lines of the prologue, Nasar describes a shocking scene in which Nash talks to George Mackey, a colleague of his from Harvard, shortly after the first jagged teeth of schizophrenia had begun to tear his mind apart:

Nash became a worldwide celebrity as a result of the biographical film A Beautiful Mind (2001), directed by Ron Howard, in which Russell Crowe played the role of John Nash. The film was based on Nash’s excellent biography written by Sylvia Nasar and published in 1998; in the first lines of the prologue, Nasar describes a shocking scene in which Nash talks to George Mackey, a colleague of his from Harvard, shortly after the first jagged teeth of schizophrenia had begun to tear his mind apart:

“Mackey couldn’t keep it down any longer; his voice sounded slightly whiny, but he made an effort to be friendly:

»–How is this possible? –he began to say, “How is it possible that you, a mathematician, a man devoted to reason and logical demonstration… how is it possible that you believed that aliens were sending you messages? How can you have believed that aliens had recruited you to save the world? How is it possible…?”

»Nash finally looked up and stared at Mackey, without blinking and with a look as cold and inexpressive as that of a bird or a snake; then, as if he were speaking to himself, in a reasonable tone and with his slow and gentle southern cadence, he said:

“Because the ideas I conceived about supernatural beings came to me in the same way as my mathematical ideas did, and for that reason I took them seriously.

Nash received the Abel Award in 2015 for the outstanding mathematical results he had achieved before he fell ill. He died in a car accident in the United States on his way home from the airport after collecting the prize in Norway.

References:

Antonio J. Durán, Crónicas matemáticas, Crítica, Barcelona, 2018.

Leave a Reply