In the mid-17th century, Europe experienced the last epidemics of bubonic plague.

In Seville the main crisis occurred in 1649 (and which is so well recreated in the TV series by Alberto Rodríguez and Rafael Cobos), as a result of which an estimated 40% of the population died; it was the coup de grace for a city already in decline, which from then on ceased to be among the leading cities in Europe.

In London, the main crisis occurred fifteen years later, between 1665 and 1666. Deaths there may have reached 25% of the population, but the epidemic was not enough to halt the inexorable rise of a city that was to become the capital of the world.

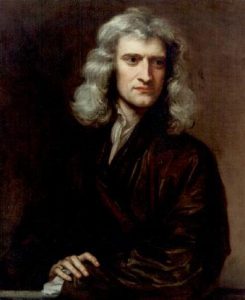

Not unrelated to this boom was the benefit that the British achieved for shipping in the wake of the scientific revolution that Newton would culminate in 1687 with the publication of the Principia. Newton himself later acknowledged that this culmination owed much to the plague epidemic of 1665. Newton was then 23 years old, the last of which he had spent studying at Cambridge University. We know that in the previous year Newton had studied almost all the important mathematical developments of the previous decades, including Descartes’ analytic geometry and some infinitesimal methods developed by mathematicians such as Wallis, Hudde, Van Heuraet and Mercator. Not that these developments were explained at the University, but the books and manuscripts where Newton studied them on his own were in circulation.

By the middle of 1665, Newton had been engaged in an intense, passionate and ardent love affair with mathematics for almost a year. It was then that the plague epidemic struck Cambridge, the University closed, and Newton returned to the calm of his home at Woolsthorpe in the Lincolnshire countryside. Within months of arriving, Newton lost interest in mathematics when mechanics, gravitation and colour theory also claimed his attention.

Between March and June 1666 he returned again to Cambridge, and then back home again, where he composed a treatise with the germ of what would later become his method of infinitesimal calculus; this treatise would not see the light of print until 1962, almost three centuries after it was composed, although copies were circulated among some English mathematicians.

According to D.T. Whiteside, the greatest expert on Newton’s mathematics: “In those two years a mathematician was born, of such genius that by the end of 1666 he stood on a par with Huygens and James Gregory, and probably above his other contemporaries”. In his later long life, Newton would not devote himself to mathematics with the intensity of that period, and the time he devoted to it in the following decades was more than anything else an extension of what he had already discovered. And according to R.S. Westfall, author of the best biography of Newton: “Had he published his discoveries, he would have left the mathematicians of Europe breathless with admiration, envy and wonder”.

In addition to infinitesimal calculus, Newton made other fundamental discoveries about the nature of light and colours and about gravitation in those 20 months of confinement in his birthplace. The law of inertia that he had learned from Descartes and Galileo, together with Kepler’s third law, led him to deduce that the forces between the planets varied inversely as the square of their distances from the Sun, although he mistakenly believed at first that these forces were centrifugal rather than attractive. After 1666, Newton lost interest in the problem of planetary motion. He briefly returned to it in 1679, this time convinced that the forces were attractive. He finally returned to gravitation in 1684, as a result of a visit by Edmund Halley to ask him what Newton thought would be the trajectory of a body attracted by another body with a force inversely proportional to the square of their distances. “Ellipses,” Newton replied. “And how do you know that?” asked Halley. “Because I have calculated it,” was Newton’s forceful reply; and there can be little doubt that the infinitesimal calculus Newton had discovered was fundamental to his investigations in mechanics and gravitation. From August 1684 until the spring of 1686, Newton concentrated on writing what was to be his magnum opus. During those two years, according to Westfall: “Newton’s life was reduced to the Principia“, and according to his assistant at the time: “So focused, so immersed was he in his studies, that he scarcely ate, or even forgot to eat”.

In a manuscript dated 1727, a few years before his death, Newton summarised his achievements during the pandemic: “Early in 1665, I discovered the method of power series and the rule for reducing any binomial to such series. In May of the same year, I discovered Gregory and Sluse’s method of tangents, and in November, I obtained the method of fluxions. In January of the following year, I developed the theory of colours, and by May, I had started working on the inverse method of fluxions. In the same year, I began to think about gravity extended to the lunar orbit, and from Kepler’s rule I deduced the forces that keep the planets in their orbits. At that time I was at the height of my genius, and mathematics and natural philosophy occupied me more than they ever would”.

References

A.J. Durán, El universo sobre nosotros, Crítica, Barcelona, 2015.

Leave a Reply