Those who have read Bertrand Russell will be familiar with the ironic, very British touch that often appears in his texts. A very varied irony, ranging from the coldest to the most acidic (and on quite a few occasions turning into sarcasm). In Human Society in Ethics and Politics, we find one such sarcasm about the usefulness of mathematics (very much in the style of G.H. Hardy, with whom he coincided at Cambridge): “Consider the teaching of mathematics. In universities, mathematics is taught mainly to men who are going to teach mathematics to men who are going to teach mathematics to… It is true that it is sometimes possible to escape from this vicious circle. Archimedes used mathematics to kill Romans, Galileo to improve the artillery of the Grand Duke of Tuscany, modern (more ambitious) physicists to exterminate the human race. It is usually for this reason that the study of mathematics is recommended to the general public as worthy of public support. This utilitarian attitude is apparently as prevalent in Soviet Russia as anywhere else. Some twenty years ago I met a Russian mathematics teacher who told me that he had once dared to suggest to his class that mathematics should not only be valued for its power to improve machines, but this remark, he told me, was regarded by the whole class with sympathetic contempt as a lingering residue of bourgeois ideology”.

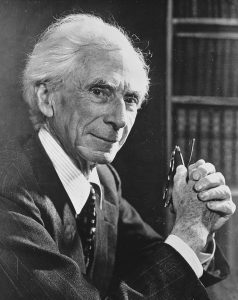

As a young man, Bertrand Russell was a leading figure in logicism, which sought to reduce mathematics to logic, and to demonstrate this he composed with his colleague Alfred N. Whitehead the monumental Principia Mathematica; eventually Russell came to recognise that the aims of such a great work were far from being achieved, and that there were vast areas of mathematics beyond logic (in a sense, everything touched by the magic of infinity). The pill I leave below, written at the time when he was composing the Principia Mathematica, offers a sample of cold irony; it is contained in one of the thousands of letters he exchanged with Ottoline Morrell, one of his youthful lovers, and Russell explains in it why mathematics was so much to his taste:

I like mathematics because it is not human and has nothing particular to do with this planet or with the whole accidental universe – because, like Spinoza’s God, it won’t love us in return.

Leave a Reply