“Archimedes will be remembered when Aeschylus is forgotten, because languages die and mathematical ideas do not. ‘Immortality’ may be a silly word, but probably a mathematician has the best chance of whatever it may mean”; that was Hardy’s writing in his A mathematician’s apology a few years before he attempted suicide.

Hardy may well have been right, for, in a way, immortality (or timelessness, if you prefer), means a great deal to a mathematical result. There is something perennial, even eternal, about a theorem, for many think that the mathematician merely discovers a truth that already existed and will, of course, continue to exist. The mathematician hopes that some of the aroma of eternity that the theorem he has discovered will end up perfuming him as well. There is, in many of those who have dedicated themselves to mathematics throughout history, an eagerness to transcend through the very object they study, that is, mathematics. And yet, the tombs of the world’s cemeteries are as full of mathematicians as they are of writers, friars, shoeshine boys or people from any other imaginable guild.

This is attested to by the large number of famous epitaphs on the tombs of mathematicians that we know of. Here are a few of them.

According to Plutarch, Archimedes explained very clearly to his relatives the epitaph he wanted for his tomb: a sphere inscribed in a cylinder was to be engraved on it, together with the ratio linking its areas and volumes; and so it was done. Legend has it that this inscription enabled Cicero, a century and a half later, to find Archimedes’ tomb in Syracuse among brambles, bushes and undergrowth. Cicero thus went down in mathematical folklore as the only Roman to have made a significant contribution to mathematics.

On the tomb of Diophantus was engraved a problem, a riddle whose solution gave the visitor the number of years the person buried there had lived; And one imagines the tomb shaded by a fig tree and the visitor recovering from the fatigues of the road with its fruits while he racked his brains to find out how long that Greek mathematician lived, to whom the gods granted him to be a boy for a sixth part of his life, and after a twelfth part more they filled his cheeks with hair; they illuminated him with the light of marriage after another seventh part of his existence, and after five more years they gave him a son. Unhappy son who only lived half the life of Diophantus, who then consoled his sorrows with the science of numbers for five more years until the grim reapers cut the thread of his life.

According to his son-in-law, Kepler’s epitaph in a Regensburg cemetery read: “I who measured the heavens, will now measure the shadows of the earth. My spirit has gone to heaven, here lies only the shadow of my body”; though only for a short time, for bad luck followed Kepler beyond death. Three years after his burial, Regensburg was taken by Swedish troops during the Thirty Years’ War, only to be recaptured by imperial troops eight months later. In the course of the fighting, Kepler’s tomb and remains were lost forever.

An outline of Jupiter and the four ‘Medicean’ moons is engraved in black marble in the ostentatious pantheon where Galileo rests in the Florentine church of the Santa Croce; Michelangelo, Machiavelli, and Gioachino Rossini are also buried there.

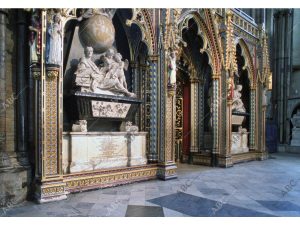

Newton’s magnificent burial was narrated by none other than Voltaire; Newton’s mortal remains lie in a charming mausoleum in Westminster Abbey. The Abbey is itself a veritable cemetery; and besides Newton, other British scientific glories, such as Darwin or Maxwell, are buried there, while others, who are not, have a monument, a tombstone or a simple commemorative tile, such as Dirac.

Jacques Bernoulli chose for his tombstone the drawing of a logarithmic spiral, like the one obtained from a golden rectangle; but someone must have made a mistake since what is engraved on his tombstone is an Archimedean spiral. Perhaps that someone was his brother Johan, also a famous mathematician, with whom Jacques had more than one quarrel, and who wanted to take posthumous revenge on his brother with this display of black and intellectual humour. But who can say?

The great Gauss was very unhappy about his epitaph: the “prince of mathematicians” wanted to have a 17-sided regular polygon engraved on his tomb, but there was no way of finding a stonemason who would commit himself, as they all complained that it would be no different from a circumference.

And no one and nothing, including Gödel’s theorems, prevented Hilbert’s famous phrase “Wir müssen wissen, wir werden wissen” (“We must know, we will know”) from being engraved on Hilbert’s tomb. It must be said, however, that it was a fitting epitaph for him.

References

A.J. Durán, Pasiones, piojos, dioses… y matemáticas, Destino, Barcelona, 2009.

Leave a Reply