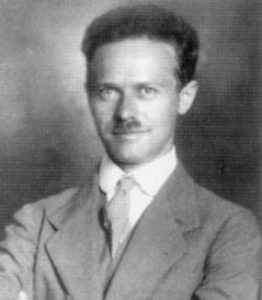

As we have already had occasion to explain in a previous post (Pi and the Nazis), the Nazi madness in Germany also reached mathematics. The main ideologue of mathematical Nazism was Ludwig Bieberbach (1886-1982).

Bieberbach had achieved a certain mathematical recognition, partly after solving the first question of problem 18 of Hilbert’s list. As a result of his well-earned reputation as a fine mathematician, Bieberbach became a professor in Zurich, Königsberg, Basel and Frankfurt; but, above all, it enabled him in 1920, at the age of 34, to obtain a professorship in Berlin. In the same year he was appointed secretary of the German Mathematical Society. Even then, Bieberbach showed signs of a furious ultra-nationalism.

In November 1933, once it became clear that Hitler was well established in power, Bieberbach joined the Sturmabteilung, or SA, the Nazi party’s paramilitary organisation. Around this time, he taught more than one class, well equipped with Nazi belts and insignia, and is known to have participated in SA parades and paraphernalia, in some cases accompanied by his children – at the time aged 11, 15, 17 and 18.

To indoctrinate mathematicians into its racial creed, the Third Reich had, apart from the general regime, two specific tools at its disposal, controlled to a greater or lesser extent by Bieberbach. One was the mathematical camps for students – where the importance of mathematics in national and military education was discussed, how mathematics could contribute to the understanding of the Third Reich’s racial measures, and the like; the other consisted of the creation of a mathematical journal with a strong racial content, Deutsche Mathematik, which was published from 1936 to 1944.

From January 1937 onwards, Bierberbach lost support in the regime. Partly because of this, partly because of the costs incurred by a persistent overrun of the planned number of pages, the official funding of the journal Deutsche Mathematik was to be cut back. Bieberbach defended it fiercely, citing the fact that it served as an ideological mainstay of the mathematical community, but above all, he appealed to the counterbalancing effect it had on the other German mathematical journals, which, according to Bieberbach, were not very scrupulous about adhering to the “racial creed of the Third Reich”. In a report Bieberbach claimed: “One of these journals still has a Jewish editor. Another devotes articles to Jewish women and communists. A third publishes articles by ‘émigré’ Germans. And a fourth is edited by a Jew and a half-breed ‘émigré'”.

Let us name those denounced by Bieberbach.

The “half-breed émigré” was none other than Otto Neugebauer, the great historian of mathematics and founder of both Zentralblatt für Mathematik (in 1931, together with Richard Courant and Harald Bohr) and Mathematical Reviews (in 1940, when already settled in the USA). Those scientists to whom Bieberbach refers with the euphemism “émigrés” were the German scientists expelled by the racial laws of the Third Reich; their loss caused a bloodletting from which, in particular, German mathematics could not recover.

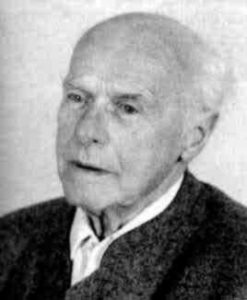

But it was many of those expelled who were never really able to recover. One of the Jewish editors to whom Bieberbach refers was Otto Blumenthal, Hilbert’s first disciple, who in 1937 was still editor of Mathematische Annalen. Blumenthal was born in Frankfurt in 1876 and during World War I was in charge of some military weather stations. Blumenthal was one of those who fought hardest after the war to bring German mathematics back onto the international stage. Until 1938 he weathered the anti-Semitic storm as best he could, and also the accusations of being a communist – for which he was imprisoned for a few weeks. But in 1938 he had to leave Mathematische Annalen – as Bieberbach had requested – and in 1939 he was also expelled from the German Mathematical Society. In July of that year he went to Utrecht with his wife, where they lived on charity until 1943, when they were interned in a concentration camp; his wife was exterminated that same year, and he a few months later.

Each of Bieberbach’s criticisms and slanders conceals a deep evil. All these evils together give a full picture of the destruction that the Nazis perpetrated on the fabric of German science. Perhaps there was no need for such accusations from Bieberbach for the Nazi racial shredder to work, though perhaps it was because there were people like him that the shredder reached the terrifying levels of precision and effectiveness that it did. It is impossible to explain the scale of Nazi barbarism between 1933 and 1945 if it is presented as the work of one madman or, at most, a small gang of madmen. Without a comprehensive and well-structured system of collaborators, the Nazis would not have been able to implement such repressive and horrifying policies as the ethnic laws against the Jews, nor would it have been possible to carry out such a meticulous extermination as they eventually did – in germ already in those laws. It is impossible to understand that atrocious reality without admitting the metastasis of Nazism, without taking into account the social support Hitler had, without overlooking the responsibility of people like Bieberbach. And something similar can be said of what happened in Spain with Franco: without similar support from part of society, it is impossible to understand how Franco was able to carry out the brutal and meticulous repression of the Republicans during and after the civil war, and how he was able to impose an iron dictatorship that lasted forty years.

And the Jewish and communist women to whom Bieberbach refers? I will talk about one of them in the next post.

References

Antonio J. Durán, Pasiones, piojos, dioses… y matemáticas, Destino, Barcelona, 2009.

Leave a Reply