After the events in Afghanistan this August, it seems appropriate to dedicate a couple of posts to al-Bīrūnī, a mathematician who moved in that part of the world at the turn of the first to the second millennium; the reader will see that despite the thousand years that have passed, some things have not changed.

Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Bīrūnī was born in Khwārizm, the region south of the Aral Sea from which al-Khwarizmi presumably also originated. Today, al-Bīrūnī’s hometown bears his name and lies just a few kilometres northeast of Khiva, one of the most important cities, along with Samarkand and Bukhara, on the section of the Silk Road that today belongs to Uzbekistan. Al-Bīrūnī is the Muslim scientist who best represents the travelling and adventurous spirit of the Silk Road. Born in 973, he lived through a time of particular instability, wars and internal conflicts in Islam and, consequently, of difficulties for the trade routes that crossed its territories.

Al-Bīrūnī was one of the most prolific authors of medieval Islam. He is estimated to have written nearly a hundred and a fifty books, of which barely a couple of dozens have survived. He wrote about almost everything, astronomy and astrology – almost half of his output – chronology and time measurement, geography and map-making, mechanics, medicine and pharmacology, meteorology, mineralogy, history, religion and philosophy, magic and, of course, mathematics, where there are references to eight books on arithmetic – one has survived – and seven on geometry and trigonometry.

Although at this time the Khwārizm was still under the rule of Baghdad, the weakness of the caliphs meant that their authority was merely nominal, with royal control of the area being divided between various local and Persian princes and viziers who ruled small kingdoms in what are now Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Iran and Afghanistan, all of which were absorbed by an emerging power in the area, the Ghaznavids. Of Turkic origin and based at Gazni in southeastern Afghanistan, the Ghaznavids built a powerful but short-lived empire that lasted only from the mid-10th to the 12th century, stretching from the Euphrates to the Indus and Ganges valleys of northern India.

Wars and subsequent conquests in his homeland meant that the first half of al-Bīrūnī’s life was spent bouncing between the various courts disputing the domination of the Khwārizm. We know of many of the places he visited from the astronomical measurements he made there, or from the reports of eclipses and other ephemeris in his books. During the first forty years of his life, al-Bīrūnī lived, for varying lengths of time, in a variety of places. In Kath, near where he was born and then one of the main cities of the Khwārizm; in Rayy, an old Iranian city near present-day Tehran; in Bukhara, where al-Bīrūnī engaged in a dispute with the then young Avicenna about the nature of light and heat; in Gorgan, on the southeastern shore of the Caspian; and in Kabul. And the list is certainly not exhaustive.

At the end of the second decade of the 11th century, Mahmud, sultan of the Ghaznavids, conquered all the lands where al-Bīrūnī had been moving until then. He became a member of his court, although it is not clear what his status was. His relationship with the sultan seems never to have been good, and some –perhaps unreliable– sources claim that he was treated cruelly and arbitrarily, describing al-Bīrūnī almost as a slave who advised the sultan on matters of geography and astrology. Al-Bīrūnī then spent long periods of time in Ghazni, the Afghan city from which the new empire had taken its name, although he was yet to undertake the journey that would make him most famous as a traveller.

While extending his empire westward, conquering the Khwārizm, Mahmud also expanded it to the southeast, subduing much of the Indus and Ganges valleys, where his conquests and plundering remained only a few dozen kilometres west of Varanasi. Al-Bīrūnī then spent long years in India, travelling along the middle and upper reaches of the Indus in what is now Punjab and Kashmir. Although it is difficult to determine when and for how long, his Indian journey must have taken place between the second and third decades of the 11th century and lasted at least ten years.

He recorded his experiences in India and all that he learned there in a monumental treatise of more than 700 pages called Kitab al-Hind, or Book of India. His return to Ghazni coincided with the death of Sultan Mahmud, who was succeeded by Masood, the eldest of his sons, after a brief civil war. Al-Bīrūnī’s situation improved under the new sultan, to whom he dedicated his book on India. His travels continued, he visited his homeland at least once more, and died in Ghazni in 1050.

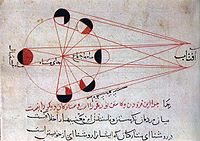

His book on India is a comprehensive portrait of what he saw on his travels along the middle and upper reaches of the Indus. It contains information on religion and philosophy: mysticism, soul, matter, paradise, hell, idols; on social and religious customs: descriptions of the Hindu caste system, marriages, rites, pilgrimages, feasts and festivals, food, superstitions, rules of chess; on literature and writing: both sacred and grammar and other matters; on science and mathematics: al-Bīrūnī included a table of contents of the Brāhma Sputha Siddhānta, the book where Brahmagupta gave zero a letter of nature as a number, and also approximations for relevant mathematical constants such as the number \(\pi \); on astronomy and time measurement: legends and theories about the universe and time, with detailed descriptions of the immense hierarchies and time cycles linked to Hinduism, and of the calculations of planetary positions, size and distance of planets, eclipses, etc. He also wrote about geography, including the description of up to sixteen of the routes he followed, with distances and geodesic data; and also about astrology. The care that al-Bīrūnī put into his Kitab al-Hind means that even today, in many rural areas of India, it is still possible to recognise many of his descriptions.

Naturally, Indian numerals are also present in al-Bīrūnī’s book on India, with a reference to the Indian parentage of the system then already used in Islam for writing numerals: “The Indians are not in the habit of making any use of their letters for calculation, as the Greeks or we ourselves did in ancient times. And just as they have different calligraphies in different parts of their countries, so do the signs of calculation vary. What we Muslims use as numerals is selected from the best and most common that the Indians have. But the forms are of little importance, as long as we know their own meaning”.

Al-Bīrūnī was a polyglot, his mother tongue was the Indo-European language, close to Persian, which was spoken in the Khwārizm, but he was fluent in Arabic and Persian; he mastered Sanskrit well enough to translate, with help, some Indian scientific books into Arabic, and vice versa, and of Greek, Syriac and Hebrew he had enough knowledge to read with the help of dictionaries. On one occasion, writing about the various languages he knew, he asserted: “It is in Arabic, translated, that the sciences have come to us from all parts of the earth, and it is thus embellished that they have entered our hearts. The beauty of the Arabic language has circulated with them through our arteries and our veins. Naturally, every nation delights in the colours of its beloved language, the language of the habitual communication that each one maintains with his friends and companions. But if I judge for myself and for my native tongue, I think that a science would be as strange to be eternalised in it as a camel in the ditch of Mecca or a giraffe among thoroughbred horses. If I compare Arabic to Persian (and I can express myself fluently in both languages) I have to confess that I prefer an offence in Arabic to a compliment in Persian. To understand what I mean, it is enough to observe what a scientific work translated into Persian becomes: it loses its lustre, its bearing declines, its features become blurred, and it ceases to be useful. Persian is only useful for conveying historical stories about ancient kings or tales for evening gatherings”.

Certainly, similar outpourings of frankness would not be to the liking of more than a few, and perhaps that is why al-Bīrūnī came to be known among Hindus as a sour person – such that, by comparison, some said, vinegar would be sweet. But was al-Bīrūnī’s personality really so sour? We will say more about this in a future post.

References

A.J. Durán, El ojo de Shiva, el sueño de Mahoma, Simbad… y los números, Destino, Barcelona, 2012.

Leave a Reply