We ended the previous post on al-Bīrūnī wondering whether al-Bīrūnī’s personality was as sour as his fame claimed. In fact, it was not so, and as far as is known, al-Bīrūnī must not have had a bad temper, but was, rather, an open-minded person; his tolerance, however, did not extend to fanatics and idiots: He despised the Arab conquerors of his native land because they destroyed so many ancient books, and ridiculed muezzins who, suspicious in their ignorance, refused the help which astronomy and trigonometry could offer them in determining the hours of prayers: “We cannot trust those muezzins whose hearts are disgusted at the mere mention of shadows, trigonometric functions or altitudes, who get goose bumps at the mere mention of a calculation or a scientific instrument. And we cannot trust them when we have to deal with the hours of prayer, not because they are unfaithful or treacherous, but because of their sheer ignorance”.

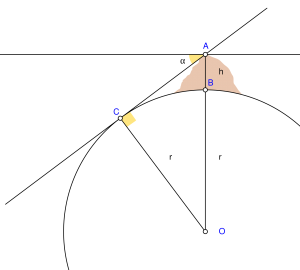

Islam is particularly sensitive to this issue of prayers, as one of its basic pillars establishes five daily ritual prayers. Given what the Prophet Muhammad told his followers, the timing of these prayers became a serious problem, with a clear astronomical and trigonometric component. The afternoon prayer, for example, corresponds to the prayer that Muhammad performed at the Kaaba with the archangel Gabriel; by the Prophet’s own admission, on the first day this prayer took place “when the shadow of any object is equal to the object”, while on the second day it occurred “when the shadow of any object is twice the shadow of the object”. The inherent dynamics of religious belief cause believers to attribute to a prophet’s words a degree of absolute infallibility, so the evening prayer must have taken place between those two precise moments: after the shadow equals the height of an object and before it is twice as long. Curiosity about the length that shadows can reach has been reflected in the most diverse cultures. The Greek philosopher Thales famously measured the Egyptian pyramids using the length of their shadows. This curiosity, which has become an obsession, is also found in Marco Polo’s Book of the Marvels of the World. In a chapter devoted to the Indian Brahmins, Polo claimed that they used the shadow as a mercantile advisor: “If it happens that they make a market for some merchandise, the Brahmin who wants to buy it stands up, looks at his shadow in the sun and says to himself: What day is it today? After the answer he then measures his shadow, and if he finds it as long as it should be on that day, he concludes the deal; but if the shadow is not as long as it should be, he does not conclude the deal, but waits until it is at the point ordained by his law”. The custom described may be spurious, but it illustrates a problem, that of calculating the length of the shadow cast by a body, which has troubled people in almost all latitudes.

Al-Bīrūnī wrote an entire book on shadows, which Roberto Casati, author of The Discovery of the Shadow, called “the most important book on shadow ever written”. Its thirty chapters reviewed everything that was known at the time about the shadow, from philosophical and poetic conceptions of the shadow – where al-Bīrūnī included numerous descriptions by Arab poets of all kinds of shadows – to a complete trigonometric treatise on how to calculate the length of the shadow at different latitudes and times of the year, or how to calculate distances between celestial bodies using shadows. Chapters 25 and 26 of the book were devoted by al-Bīrūnī to determining the times of Muslim prayers.

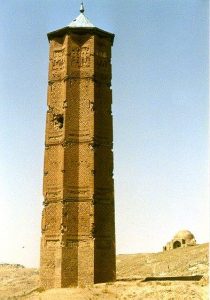

Al-Bīrūnī had to deal with the circumstance that Muhammad’s prescription for afternoon prayer leaves all those territories situated close enough to the poles that the low altitude of the sun means that the shadow cast by an object is always more than twice its size without a time for prayer. It happened, in fact, that the Sultan once received Turkish ambassadors from the Volga. The delegation told him that in the upper reaches of the river there were areas where the sun barely lifted an inch off the ground at midday, causing bodies to cast almost endless shadows. “That is heresy,” cried a court imam, “for one could not then pray the evening prayer.” Al-Bīrūnī was more sympathetic than the imam. He explained to the sultan that the earth is a sphere and that its curvature means that near the poles the low altitude of the sun causes the shadows to expand. He also explained that the Prophet’s prescriptions were for the territories situated in the latitudes of Mecca, and that one should be guided by trigonometry in order to establish the corresponding timetable according to latitude. Al-Bīrūnī was irritated by ignorance and fanaticism, which led him into more than one confrontation with the Muslim clergy. He once recommended the use of a solar calendar, instead of the lunar calendar prescribed by Muhammad, for the calculation of the shadows; a muezzin reprimanded him for this, on the grounds that it was tantamount to imitating the infidels. “The infidels eat,” al-Bīrūnī replied, displaying the acidity that the Indians attributed to him, “should we also cease to imitate them in that?”

In his book about India, al-Bīrūnī told the following interesting story, which is very illustrative of the value and usefulness of religious symbols, of what may or may not be considered offensive, and of irreverence and ignorance. In one of his war raids in the Ganges valley, Sultan Mahmud took as booty some ‘lingas’, which he later placed at the gates of the Gazni mosque. The ‘linga’ is a stylised representation of the erect phallus, and according to Massimo Raveri in his History of Religions: “it is the most refined, austere and yet intense representation of Shiva” – together with Brahma and Vishnu, Shiva forms the primary trinity of Hindu gods. It so happened that the Muslim faithful who went to pray at the Gazni mosque, not knowing very well that those sculptures that the sultan had planted there were the most refined and austere representation of Shiva and the veneration that the Hindus professed for him, or precisely because they knew it, ended up using the ‘lingas’ to scratch their feet.

References

A.J. Durán, El ojo de Shiva, el sueño de Mahoma, Simbad… y los números, Destino, Barcelona, 2012.

Leave a Reply