The morning of May 9th 1943 was particularly harsh in Palermo because of the intensity of the bombing raids by American aircrafts. Allied troops had landed in Sicily a few months earlier and were seeking to complete their conquest of the island.

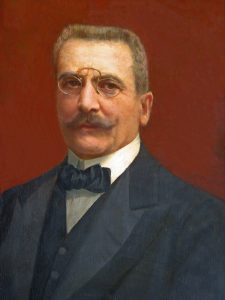

Among the many buildings destroyed were two palaces: one belonging to the historical character on which the famous novel “The Leopard” is based, the Prince of Lampedusa, Giulio Fabrizio Tomasi, and the other to an important Sicilian mathematician, Giovanni Battista Guccia. Both characters were extreme in their respective specialities: nobility and mathematics. They were also related to each other: uncle and nephew.

Guccia’s palace housed the printing house where the prestigious mathematical research journal Rendiconti del Circolo Matematico di Palermo, –which Guccia had founded some sixty years earlier– was published. At the age of thirty and with a doctoral thesis on geometry of surfaces, Guccia decided to return from Rome, where he had studied, to his beloved and distant island. Jobless (but by no means penniless), he founded a mathematical society, which he called the Circolo Matematico di Palermo. It was 1884 and he was joined by 27 people, including mathematics teachers, engineers and architects.

Thirty years later, in 1914, the Circolo Matematico di Palermo was the largest mathematical society in the world: it had 914 members, of all nationalities and countries (the French society had 298 and the German society 769), and the journal Rendiconti del Circolo Matematico di Palermo was the mathematical journal with the world’s largest circulation. The scientific prestige of the society and its journal is reflected in the financial aid it received from the Rockefeller Foundation after the First World War to survive (due to the crisis caused by the depreciation of the currency).

All this was the accomplishment of just one person: Giovanni Battista Guccia. He was a refined aristocrat who devoted himself to mathematics thanks to the encouragement of his uncle, the Prince of Lampedusa, who had a first-class astronomical observatory in his summer palace. After his doctoral thesis, Guccia faced with the alternative of research, chose to devote himself to running a mathematical society and editing a mathematical research journal. He was helped by his keen scientific instinct (inherited from his teacher, the geometer Luigi Cremona) and his personal knowledge of the best mathematicians of the time: Mittag-Leffler, Poincaré, Jordan, Landau, Volterra… Also the judicious application of his fortune to his mathematical interests: he bought a printing press, which he set up in the basement of his palace, to directly control the quality of the journal. Many of the best mathematical results of the first third of the 20th century were published in Guccia’s Rendiconti.

But then came the decline: Guccia died in 1914, Mussolini’s racial laws of the 1930s excluded foreigners from the journal’s editorial board, and, finally, bombs destroyed the printing press.

Guccia is now barely remembered. In Palermo there are two streets named after him and a palace, which belonged to his paternal grandfather (who was, at the same time, his maternal great-great-grandfather). Guccia’s palace carries a Palermo legend: only the adjoining building of the journal (which at the time was another one) was bombed.

The full story of Guccia, the mathematical society and the magazine can be read at:

“Giovanni Battista Guccia” by Benedetto Bongiorno and Guillermo Curbera. Springer, 2018. ISBN: 978-3-319-78667-4. https://www.springer.com/gp/book/9783319786667

Leave a Reply