I wrote a previous post on some aspects of Felix Hausdorff’s intellectual output, both mathematical as well as literary. And I finished just as he retired from the University of Bonn in 1935 and, as he had predicted a few years earlier, things were beginning to change in Germany.

Especially since Hitler, after gaining absolute power in Germany, passed the first ethnic exclusion laws. Specifically, on 7 April 1933, a civil service reform law was promulgated that prevented Jews from working for the state administration; those who had done so up to that point were dismissed. By 1935, almost a third of the mathematics professors at German universities had been expelled. At Göttingen, for example, the ethnic policies of the Third Reich had amputated such notables as Richard Courant, Edmund Landau, Emmy Noether or Hermann Weyl – the list is not exhaustive. Many of them belonged to the school of David Hilbert, who had not allowed any prejudice, be it nationalistic, racial or sexual, to affect his selection of students or collaborators, and who with so much effort and commitment had succeeded in making Göttingen the mathematical centre of the world; in just a few months, Göttingen had become practically nothing. “When I was young,” said Hilbert, who was 71 years old at the time, “I decided that I would never repeat what I had heard so many older people say: ‘those were the good old days and not these days’. I decided that I would never say that when I was old. But now I have no choice but to say it.”

However, the law of 7 April included some exemption clauses: those Jews who had distinguished themselves as German patriots – for example, those who had participated as soldiers in the First World War – were exempted and could continue to be public servants. This was the case with Hausdorff. He never concealed his Jewish origins; and it is not that his writings abounded in religious questions, which they did not, and when he did, there were many more pages on Eastern religions than on Judaism or Christianity. His wife, Charlotte Goldschmidt, whom he married in 1899 and by whom he had a daughter, Lenore, had converted to Lutheranism in her youth.

Possibly, had the University of Bonn expelled Hausdorff, things would have been different for him and his wife. But Hausdorff considered himself a patriot who, in his youth, just after graduating, had served for several years as a volunteer in the German infantry: there he reached the rank of vice-sergeant; so he was exempted from the law of 7 April and remained a professor in Bonn until his retirement on grounds of age in March 1935.

His ordeal had only just begun. In April 1941, a colleague of Hausdorff’s wrote about him and his wife: “Things are going tolerably well for the Hausdorffs, although they cannot, of course, escape the harassment and agitation caused by the continuous anti-Semitic legalisms. The tax and monetary burdens imposed on them are so high that they cannot live on their retirement salary and have had to dip into their savings, which fortunately they still had. They have also been forced to give up part of their house and too many people now live there […] It is certainly encouraging that some musician still visits them to play with Hausdorff: at least that brings some joy into their home”.

In October 1941, the Hausdorffs were forced to wear the Star of David, and towards the end of the year they received the news that they would be deported to Cologne: this was the preliminary to internment in the concentration camps Hitler had set up in Poland. The threat seemed to fade in the New Year, but only to give way to a new one: in mid-January they were told that on the 29th of that month they would be interned in a suburb of Bonn called Endenich; again, the step prior to internment in an extermination camp.

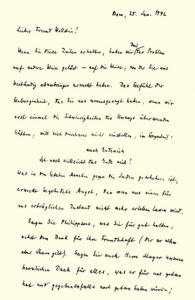

A letter that Hausdorff wrote on Sunday, 25 January 1942 has survived; in it he wrote: “Auch Endenich ist noch vielleicht das Ende nich”. The sentence is a macabre play on the words “Endenich”, a district of Bonn, and “ende” and “nicht” meaning “end” and “not”: “Although Endenich may not yet be the end”. Hausdorff, being an amateur musician, surely knew that in Endenich there was an insane asylum run by a certain Dr. Richarz – perhaps no longer in existence in 1942 – a gloomy place where the composer Robert Schumann (1810-1856) spent the last two years of his life locked up. A bad omen indeed.

So “Although Endenich may not yet be the end” is a pun. One of the most cruelly ironic rhetoric ever written, because the Hausdorffs had decided to commit suicide: “By the time you receive these lines,” reads the letter of 25 January, “we shall have solved our problem; though it will be in the way in which you have tirelessly tried to dissuade us […] What has been done against the Jews in the last few months has plunged us into the greatest sorrow, because we have been placed in an intolerable situation […]. Thank Mr. Mayer from the bottom of our hearts, for all that he did for us, but also for all that he would certainly have done; we marvel most sincerely at the achievements and successes of his organisation and, had we not been struck by this gloom, we would have taken refuge in his care; it would certainly have given us a feeling of relative security, although unfortunately it would have been relative – Hausdorff was right: this Mr. Mayer, a lawyer, died in Auschwitz […]. If possible, we want our bodies to be cremated; I enclose three statements to that effect. If that is not possible, let Mr. Mayer or Mr. Goldschmidt do what they can (please note that my wife and sister-in-law are Lutherans). My wife has already had her burial expenses paid by a Protestant foundation (you will find the documents in her bedroom). Whatever remains to be paid will be paid by my daughter Nora. Forgive us for causing you trouble even after death. I am convinced that you will do what you can, which may not be much. Forgive our desertion! We wish you and all our friends a better future”.

In this letter, written hours before he committed suicide, Hausdorff showed an impressive presence of mind. Hausdorff had written about suicide a few times before, and perhaps these reflections helped him to face his own, although who can say what will or will not work when the time comes. In 1899, Hausdorff had published an essay entitled Death and Return, which was strongly influenced by Nietzsche’s thoughts on “free death”. In the farewell letter Hausdorff wrote on the morning of his death, Zarathustra’s slogans echo loudly. “Die in time!”, Hausdorff’s sentences seem to cry out to us, as if he wanted to teach us with the dignity of his conduct that “he who fulfils himself completely dies his death victoriously”. Hausdorff was no longer willing to “hang withered wreaths on the shrine of life”, so he chose “free death, which comes to me because I want it”.

On the same evening that he wrote this letter, Hausdorff, his wife Charlotte and her sister Edith took an overdose of veronal. It seems that his wishes were granted, because his remains were cremated and the ashes placed in the Poppelsdorf cemetery.

On the same evening that he wrote this letter, Hausdorff, his wife Charlotte and her sister Edith took an overdose of veronal. It seems that his wishes were granted, because his remains were cremated and the ashes placed in the Poppelsdorf cemetery.

References

Czyż, J., Paradoxes of measures and dimensions originating in Felix Hausdorff’s ideas, World Scientific, Londres, 1994.

Durán, Antonio J., Pasiones, piojos, dioses … y matemáticas, Destino, Barcelona, 2009.

Durán, Antonio J., La poesía de los números, RBA, Barcelona, 2010.

Segal, S.L., Mathematicians under the nazis, Princeton University Press, Princeton, 2003.

Leave a Reply