Russians born in the 1880s were not a lucky generation. Having to adapt to the whole series of changes brought about by the end of Tsarism, World War I, the Russian Revolution and the subsequent mutations in the USSR, when they were already 34 years old (as in Luzin’s case) in 1917… Very complicated business.

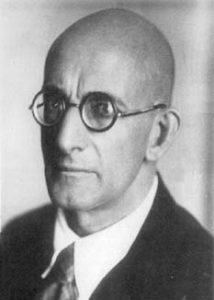

Nikolai N. Luzin created a powerful school of function theory, the Moscow school, especially during the 1920s. Among his disciples were such outstanding mathematicians as Pavel Aleksandrov, Andrei Kolmogorov, Aleksandr Khinchinin (or Jinchin), Mikhail Lavrentiev and Pavel Uryson (or Urysohn). The brilliant group gathered around him was cleverly called the Lusitania, but the group disintegrated in the terrible 1930s. Apart from this, Luzin was one of the greatest specialists in function theory and set theory of the first third of the 20th century. The development of descriptive set theory, in particular results on analytic and projective sets, owes much to him.

In 1930 an important book by Nikolai Luzin, Leçons sur les ensembles analytiques, was published in Paris, with a Preface by Lebesgue. Three serious mistakes! Namely, publishing in French, publishing abroad, and allowing Lebesgue to comment on how Luzin mixed philosophical considerations with mathematical ideas in his work. All these things were the grounds on which the great Siberian mathematician was on trial in the summer of 1936, in a sadly famous case that has come to be known as the Luzin affair. The summary trial to which Luzin was subjected was dreadful, based on insinuations and accusations with little or no foundation, with most of Moscow’s mathematicians parading as witnesses or accusers; it was the icing on the cake for him, after several years of constant fear, and an absolutely clear message to the mathematical community.

Already earlier, in 1930, a group of young people within the Moscow Mathematical Society had proclaimed that there were counter-revolutionary elements among the members of the Moscow School. Lebesgue’s Preface was quoted incriminatingly. Luzin’s former teacher, Egorov, had been arrested and sent to prison in Kazan because of his religious views (which he continued to uphold). Egorov died in 1931 after going on hunger strike in protest against his conditions. Luzin took a little longer, but in 1936 he was widely criticised in the press (including articles in Pravda) and was tried by a commission of the Soviet Academy of Sciences, accused of being an enemy of the people. Among his most aggressive accusers was Pavel Aleksandrov, his former student.

The reasons that led Aleksandrov to behave as he did are very obscure: These may have included old quarrels or grudges, the belief that Luzin was too authoritarian and not always supportive of his students, but also methodological reasons linked to set theory and ideological issues linked to Luzin’s disagreement with many aspects of the new regime… But it seems very likely that Aleksandrov was pressured by the police and used by Stalinism because of details of his personal life (namely his homosexuality, which was declared a crime in Stalin’s Russia). Luzin’s life was on the line for a few moments, but in the end he was pardoned, it is believed, with the intervention of the regime’s high authorities, probably moved by relevant scientists (the physicist Pyotr Kapitsa above all).

Luzin did not lose his seat in the Academy of Sciences, but he certainly lost his influence; nor was he rehabilitated, even in the period of liberalisation after Stalin’s death. Among those who benefited in practice from the death of Egorov and the removal of Luzin were undoubtedly the two names mentioned above. Another Stalinist casualty was Pavel Florensky, a mathematically trained philosopher and theologian, a good friend of Egorov and Luzin, a companion of theirs in religious matters connected with the ‘Veneration of the Name’. But his story would be a separate matter; I limit myself to commenting that he was one of the intellectuals most admired by Grothendieck.

I was a little cryptic earlier, so I will give details on the subject of the students and on the methodological question. In 1916, working at Luzin’s Seminar, one of his first students, Mikhail Y. Suslin, found an error in an important memoir by Lebesgue (1905) on analytically representable functions. Lebesgue had claimed that the projection of a Borel set (in R2) is Borel, but Suslin found a counterexample. This opened the way for the study of analytic sets, which both Luzin and Suslin undertook, proving their main properties (which extend those of Borel sets). But Suslin was only able to publish one paper (1917) as he died of typhus in the epidemic that struck Moscow in 1919. During the witch-hunt of the 1930s, some members of Lusitania accused Luzin of having appropriated his pupil’s results, and even insinuated (absurdly) that he had contributed to his death.

Kolmogorov also complained about some of his work being set aside by Luzin for not liking the methodology used; and Aleksandrov had a bitter complaint that Luzin had embarked on trying to prove the Continuum Hypothesis in 1916, when he was very young, which caused him to fail and abandon mathematics for a time. (Luzin, somewhat mystically as we know, is known to have had a vision in a dream that a gifted young man would appear before him, who was called upon to solve the Continuum Problem). On matters of methodology, Luzin shared the skeptical doubts of the French about set theory, and believed that some problems about projective sets would never be solved. In a word, Luzin had constructivist or semi-intuitionist tendencies, he was an “idealist” as he was accused in 1936, while Aleksandrov was a follower of Hilbert, confident in the full objectivity of set theory and topology. Incidentally, Luzin’s belief turned out to be correct in the sense that the projective set problems in question are independent of the ZFC axioms.

I cannot resist quoting a passage from Aleksandrov which gives an idea of the fury he displayed against Luzin and the hatred he always harboured for him. In some autobiographical pages (from 1979) he recalls the golden days of ‘Luzitania’ in the 1920s, but says that Luzin’s high point was 1914 and 1915, “his first creative years”. They saw “an inspiring master who lived only for and by his science”, in “the realm of the highest human spiritual values”. Then, he goes on to say, Luzin left that realm and committed evils that inevitably brought him his corresponding punishment, for “all guilt finds its punishment on earth” (quote from Goethe, in a poem set to music by Liszt, Schubert and others: ‘Who never ate his bread with tears’). And he ends: “In the last years of his life Luzin drank to the bottom the bitter cup of that vengeance to which Goethe alludes”. But one wonders whether it was not really Aleksandrov who drank from the cup in abundance.

The Luzin affair was one among a whole series of attacks on theories such as genetics, theories of relativity, cybernetics, and other forms of “bourgeois pseudo-science” rejected in Stalin’s dark ages, the 1930s and 1940s. For more on these topics, interesting details can be found in the book by L. Graham and J.-M. Kantor, The Name of Infinity. The Luzin affair has been discussed by several Russian mathematicians, such as G. G. Lorentz and S. S. Kutateladze. Florenski is discussed in the volume edited by F. Zalamea, Rondas en Sais, ensayos sobre matemáticas y cultura contemporánea (Editorial de la Universidad Nacional de Colombia).

Leave a Reply