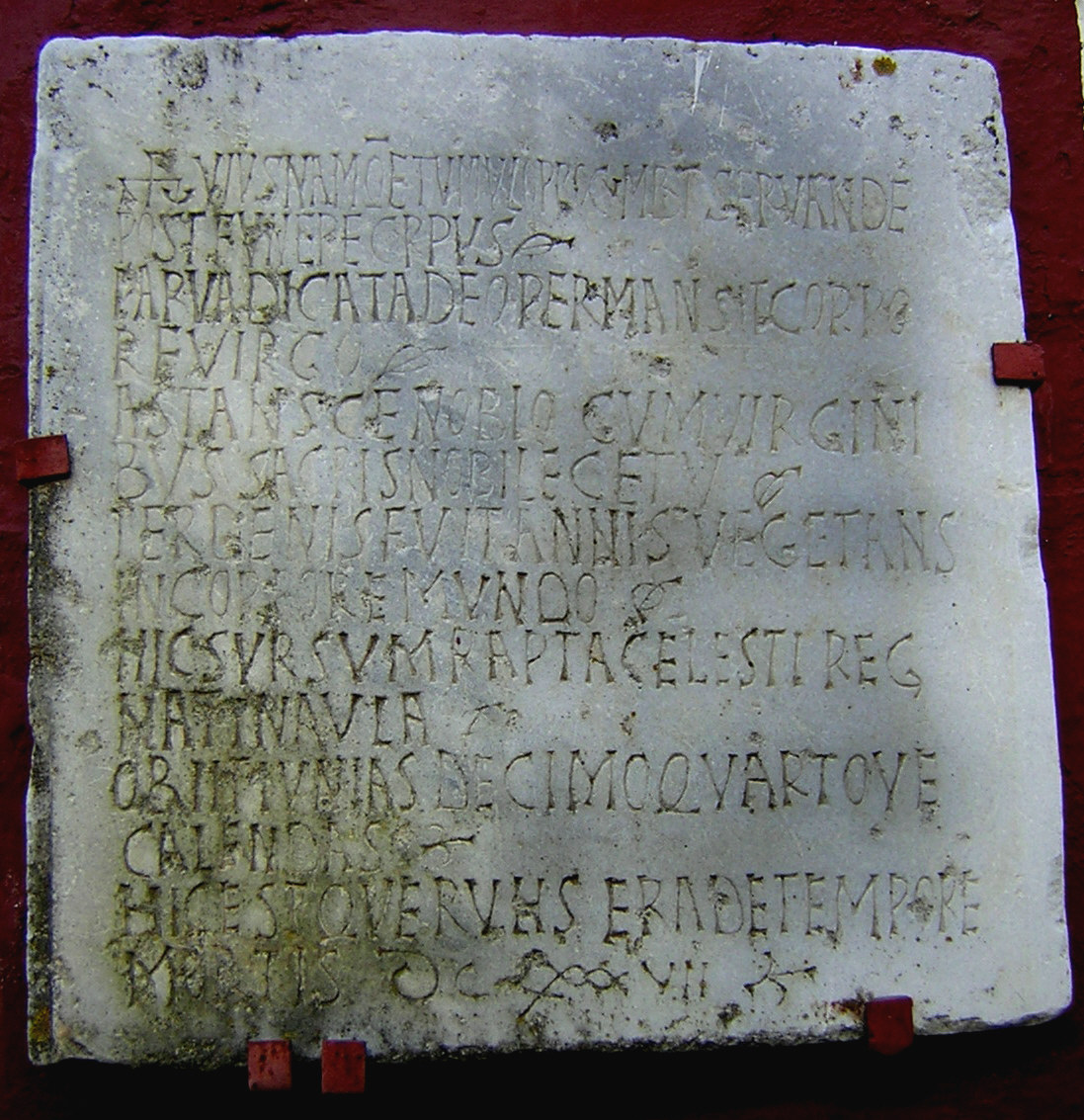

Epitaph of Servanda

Reference CLE 722 | Description | Lyrics | Location | Chronology | Epigraphic edition | Translation | Apparatus | Comentary | Type of verse | Text divided into verses and metric signs | Images | Bibliography | Link to DB | Author |

Epitaph of Servanda

Description

- Idno filename 22/01/0033

- Type of inscription: Sepulcralis Christ.

- Support: Placa

- Material: Mármol Material Description: White in colour.

- Conservation status: The right side is much shallower (4 at the top and 2 at the bottom), probably as a result of having been removed from its original location.

- Dimensions height/width/depth (cm): 60/60/9

-

Epigraphic field:

- Layout: The difference between verse and prose is indicated by a graphic sign: the lapicide has ended what he perhaps considered to be "authentic hexameters" with "hederae", while ll. 11-14 end with "hederae mucronatae".

- Decoration: The inscription begins with a "crux", crowned by a hedera and from whose arms hang the alpha and the omega, in such a way that the sign is somewhat similar to an H with only a shaft and a half; since the first word of the inscription is "uius", with a conspicuous absence of the initial h- because it is a deictic at the absolute beginning of the inscription, it is possible that this initial cross-crismon is an ambivalent sign with the double meaning of clarifying the Christian origin of the inscription and serving as an initial h-.

Lyrics

- Font:Visigoda

- Letter size:4 and 3,5 cm

- Description of the letters:The lettering is fairly regular with no visible lines.

Location

- Place of discovery: The inscription was embedded in a wall of the cloister of the Augustinian nuns of Medina-Sidonia, where it was first copied by Velázquez (ms. which is the first one cited by IHC), but neither its provenance nor its original location is known. It is not unlikely, given the condition of the deceased, that the plaque was in the first monastery we know of in Medina-Sidonia, governed by the rule of Saint Leander, who is mentioned in the Second Council of Seville (canon XI), presided over by Isidore of Seville, on 13 November 619. From that wall it passed to Don José Pardo, resident in the Palace of the Duke of Medina-Sidonia and when ROMERO DE TORRES 1934 wrote its pages and photographed it, it was still in the possession of his successor, Don Mariano Pardo de Figueroa.

- Geolocation

- Conservation location: The stone has always been owned by Don Mariano's family, passing from Medina-Sidonia, first to Jerez de la Frontera, and then to Seville, to the Hacienda Santa Eufemia, in the municipality of Tomares, owned by D. Pedro Ybarra (parish priest of Santa Cruz de Sevilla) and his sister Mª Josefa, grand-nephews and grand-nephews of D. Mariano Pardo de Figueroa, where it is now located.

- Location with Modern Nomenclature España / Cádiz / Medina-Sidonia

- Location with Old Nomenclature Hispania / Baetica / Hispalensis / Gades

Chronology

- Inscription's dating: The year 649

- Dating explanation: The inscription is dated for the Hispanic era: 19 May 649.

Type of verse

- Type of verse: Dactílico (hexámetro)

- Verse/line correspondence: No

- Prose/verse distinction: No

Epigraphic edition

⊂crux cum chrismo⊃

(H)uius namq(u)e tumulo procumbit Servand(a)e

post funere corpus ❦

parva dicata Deo permansit corpo-

5 re virgo ❦

astans c(o)enobio cum virgini

bus sacris nobile c(o)etu ❦

ter denis fuit annis vegetans

in corpore mundo ❦

10 hic sursum rapta c(a)elesti reg-

nat in aula

obiit Iunias decimoquartove (sic!)

calendas ⊂crux⊃

hic est qu(a)eru⁽li⁾s era de tempore

15 mortis DCLXXXVII ⊂crux⊃

Text divided into verses and metric signs

Huius namque tumulo procumbit Servandae post funere corpus. ll|lkkk|l/l|ll|ll|l/l|lkk|l~

Parva dicata Deo permansit corpore virgo, lkk|lkk|l/l|ll|lkk|l~

astans coenobio cum virginibus sacris nobile coetu. ll|lkk|l/l|lkk|l/kl|lkk|l~

Ter denis fuit annis vegetans in corpore mundo, ll|l/k|k/l|l/kk|ll|lkk|l~

5 hic sursum rapta caelesti regnat in aula. ll|l/l|k/l|ll|lkk|l~

Obiit Iunias decimo quartove calendas: kkl|lk|l/kk|l/l|lkk|l~

hic est quaerulis aera de tempore mortis. ll|lk|l/l|k/l|lkk|l~

Translation

“The body of Servanda lies in this tomb after her death. From her childhood, devoted to God, she kept her body virgin, living in a monastery, a noble retreat, with other consecrated virgins. She lived until thirty years in an immaculate body, snatched from here to above she reigns in a heavenly palace. She died on the fourteenth day before the Kalends of June. For those who wish to know the time of her death, here it is: era 687.”

Bibliography

Hübner, IHC 86 (inde CLE 722; Diehl, ILCV 1695; Vives, ICERV 286); id., IHC Suppl. 42; Gómez Pallarès – del Hoyo – Martín Camacho 2005, CA4; Gómez Pallarès in Fernández Martínez, CLEB, CA4, cum im. phot, qui in linguam Hispanicam vertit (inde HEp 2011,60). – Cf. Romero de Torres 1909, 94–96; id. 1934, 261–262; Mariner 1952, 15, 77, 83, 85, 87, 96, 99–100 et 101–102; Salvador 1998, 321; Castillo Maldonado 1999, 293; Menéndez Pidal 1976, 324.

Apparatus

9 Hi(n)c inepte Romero; eclesti Romero errore typographico.

Comentary

These hexameters are halfway between quantitative and stressed metre. L. 2 is quantitative; the rest have different errors in syllable count. All the clausulae are correct. Ll. 2, 5 and 7 present leonine rhyme between the penthemimers and the end of the verse; ll. 1, 3 and 4 have an extra foot. Mariner 1952, 15, also comments, with reference to l.5, híc sursúm raptá celésti régnat in áula, that the <a> of raptá could be lengthened in arsis before a caesura, or might be an echo of the adaptation of a man’s epitaph in which hypothetically raptús would be correct.

It is a dedicated poem contemplating the deceased’s sacrifice to God in the form of the preservation of her virginity. We can find no parallels, in connection with this idea, with the association between the “humility” of the nun and the great honour granted by God by admitting her to “his” convent. For a correct interpretation of the syntagma in corpore mundo, it is sufficient to refer to the texts of Ambr. exc. Sat. 1,52 and Aug., fid. et op., 10,15 Finally, for l.5, sursum rapta…regnat in aula, the underlying idea could be that expressed in Carm., adv. Marc., 1,239-242.

Linguistically, h is ommited; monophthonging of dipthongs. Servande for Servandae, cetu for coetu, querulis for quaerulis; confusion of prepositional regimes (post funere) or prepositional phrases which replace the value of some casual endings (de tempore for a genitive, already pointed out by Mariner, pp.99-100). In l. 9, hic could be there for hinc, for having forgotten the pneumatic abbreviation: or perhaps because of an eventual confusion of casual distinctions, which would have had an impact on the adverbs. En l. 11, quartoue for quartoque, because of an error of the cutter or, more probably (cf. Väänänen 1975, 250-251), because of the tendency of the enclectic –que to disappear from the colloquial use and, as a consequence, to gradually lose the value it had.

As for the onomastics, Servanda is a well known in the early Christian onomastics and both F. Salvador Ventura and P. Castillo Maldonado (above mentioned) document it well.

Author

- Author:J. Gómez Pallarès

- Last Update2023-12-04 16:36:49

- Autopsy date:2007

You can download this